by Sam Wise.

The WNOs Migrations is an opera of bold ambitions; to weave together different stories of migration into a compelling, engaging whole which changes the thinking of the audience forever. It fails, on all counts.

Before we go further, it Is important to say that the musicians and singers bear no responsibility. The orchestra were wonderful, the sitar and tabla players in particular were outstanding, and the singers were powerful, technically flawless, and note perfect. They were simply given nothing to work with. Indeed, I think that the composer Will Todd was given an impossible task, and sadly failed to rescue anything from it.

You might forgive this woeful production if it did any one of a number of things well. If it produced memorable and stirring arias, poetically beautiful libretto that moves the heart, if it taught you something about history, if it changed your perspective. It did none of these. Todd had to wrangle the work of six different librettists to create this unwieldy behemoth, and it’s clear that none of these six were restrained by a need to work within any kind of song form, meter or rhyme. They wrote, almost as a whole, prose, and yet even with the challenges of writing for music removed, that prose was stilted, ham-fisted and clumsy. You had the feeling you were watching a GCSE project, except for the couple of occasions where the whole thing went CBeebies, of which more soon. The six writers created six different themes through the piece, so let’s take each in its own place, before we come to the quite extraordinary finale.

Theme – Mayflower

As the opera opens, we are introduced to the pilgrims, on the Mayflower. From the start, we are sold a narrative in which they are fleeing persecution in the hopes of a new life of freedom in the new world. The reality is that the Puritans were oppressed only in that they were not allowed to force everyone else to live by their rules. They were free to worship and live as they pleased, but what they sought in the new world was a society in which they could enforce that lifestyle on others. Quite a different founding myth for America, and perhaps one which speaks more to the culture we see there today. We are asked to feel sorry for the plight of these voluntary migrants, who are on their way to subjugate a continent, and to hold their situation against those of the other migrants to be introduced later. They are cramped on the ship, frozen and struggling after landfall, afraid of the natives (the production uses the word Indians, which is appropriate for the period, but still grates). We revisit them throughout, finally ending, shortly before the finale, with the first thanksgiving. In this scene, the settlers sing that the Indians came and they celebrated and gave thanks together, omitting altogether that those native Americans saved the settlers at New Plymouth from starvation with their intervention.

A precedent is set during our first visit to the pilgrims, in terms of the music. Chorus ensemble parts communicate the theme with a few repeated words, ham-fisted and lacking in nuance. In this case, the words are things like “freedom”, “escape”, which not only mislead us as to the pilgrims intentions, but add nothing to any understanding we might have had. Between these, the music is in the form of sung prose, lines are of many lengths, and whilst the music shifts and carries them along, There is almost no hint of melody anywhere in the entire piece. Great credit goes to the singers for learning lengthy pieces with no rhythm, meter, musical theme or melody to serve as waymarks. I could not do it.

Theme – Birds

Our second theme is Birds, and this is where things take a turn for the primary school play. The birds are portrayed by children in blue and white, with what look from a distance like sugar paper bird heads made by their parents, and holding bird models on sticks above their heads. Again and again throughout the piece, they return to the stage, Baby Bird asking endlessly whether they are nearly there yet, how will they know when they are there, and other child-in-the-back-seat questions, while the other birds reassure him that they go to the same place every year, and to just follow Daddy Bird. The sung theme words are things like (again) “freedom”, and “limitless sky”. I invite you to imagine the extraordinary richness of descriptive, emotive and moving language about the movement and life of birds which were passed over for these blunt, clumsy and naïve choices. The birds return over and over and are, to put it plainly, annoying. Their finale is that, on arrival at their rock, it is gone, submerged beneath the rising tide of glacier melt. This might seem to be the first thread which could be woven into a powerful emotional message about man’s impact on earth, but you would be disappointed. The birds are so cartoon like and annoying that all emotional impact is lost, and you find yourself glad that you at least won’t have to see them any more. Again, you will be disappointed.

Theme – Flight, Death or Fog

A third theme is introduced in the form of the story of Pero, a third generation enslaved person from the Caribbean who has been brought to Bristol by his owners. The background story here is confusing, with Pero’s wife dressed in a manner which is entirely appropriate for a Caribbean enslaved person, but also resembles the costume of a house slave in the antebellum south. This is combined by casting back to his grandfather, first taken from Africa in denim shorts, who moves between historical physicality and ghostly shade in the present as Pero ponders ending his suffering with suicide. One scene which does work to a degree portrays Pero waiting at table as his insufferably superior owners speak of him as a “specimen”, ask him to recount sale prices of other slaves, and laugh as they ask whether he is a beast masquerading as a man, or the opposite. It’s gratingly painful in its humiliation, and almost the only really emotionally impactful part of the performance for me. As Pero’s journey wraps up, we have one of the few examples of melody or song form, as Pero’s Caribbean compatriots and wife sing to him in a call and answer form which, rather than Caribbean, rings with the sound of a cotton plantation field song from the South of the USA.

Theme – Treaty Treaty 6

We are also introduced to two Cree women, who are fighting the effects of colonisation in the current day in southern Canada, a pipeline being driven across their land as they fight a court battle. The richness of first nations culture and the struggle against the encroaching consumptive and destructive culture that capitalism and white men bring with them is distilled down to “our ancestors knew this would happen,” “we are equal, not more important than the land and nature,” and “Mother! We must fight!”. Their timeline appears to cross that of the pilgrims as we approach the finale, but none of the connective tissue is there to help us understand it. We move from the pilgrims singing that they all gave thanks together, on the first thanksgiving, to the descendants of those pilgrims knocking the protesting Cree aside as they bring through their pipeline. No mention is made that the pilgrims, rather than appreciating and building community with the native Americans who saved their lives that first frozen thanksgiving, systematically betrayed, cheated and murdered them. No link is drawn between the rapacious capitalism of the pipeline builders destroying sacred land and the pilgrims belief that they were going to an empty land which God intended for them. Manifest destiny, with all its horrific results, is ignored.

Theme – The English Lesson

The next theme, Cardiff 2022, is the most successful of the whole production. We are introduced to refugees from war torn countries feeling oppression, and what they have to say feels authentic, and moving. You sense that the librettist has met these people, and is using their words. We meet a woman who was a teacher, but now, feels that she is nothing. A young man separated from his family at 18, wanting to live, rather than just stagger towards death. A woman looking for her children, who were separated from her during the escape from her country. Here, the operatic form blunts the emotional impact of the stories somewhat; these pieces could have benefited from sensitivity, vulnerability and sadness being echoed in the sung delivery, but the broad operatic vibrato and powerful delivery communicates only the grief effectively. This was the best of Migrations, and it still could have been far better.

Theme – This Is The Life

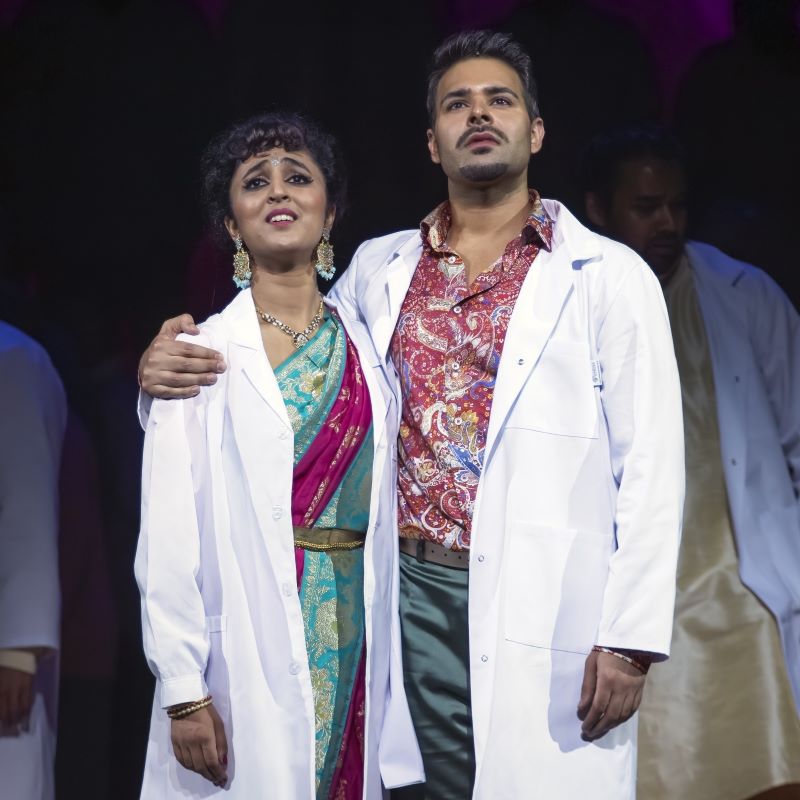

Our final theme is both the worst and the best of the evening. We open with beautifully played sitar, and a woman in silhouette, in a sari, dances with extraordinary grace. You find yourself thinking that this must be a creation myth, a Tom Bombadil, the syllable which spoke the universe into being. In fact, we discover that this woman is a doctor, one of several who have been invited to the UK to work in the NHS. This theme could not have been handled more differently than all the others. Elsewhere, all prose is sung, all trace of vernacular and accent is missing, and the music is uniformly sombre. Here, we are suddenly catapulted into a comedy packed with Bollywood sensibilities. As we learn of the poor treatment of the doctors in the country they have come to help, we are also treated to a set dressing which looks like an Indian restaurant in Brighton, and lots of bright, joyful, song and dance routines. These are delivered vibrantly, but clash so heavily with the rest of the production, as does the fairly successful humour, that we’re left floundering for things to hang on to. The doctors are serious and buttoned up when at work, and the dialogue, for dialogue there is, is spoken not sung. But the moment they are free from the trammels of the NHS, they burst into song and Bollywood dance in a way which feels almost fetishizing. The librettist for this part is at least of Indian heritage, and it’s not my place to tell her what is or isn’t fetishizing of Indian culture, but it felt jarring, whilst at the same time joyous. Another example of the stilted nature of the libretto comes here, as well. We are treated to an avatar of Enoch Powell, in a pinstripe suit, with any uncertainty about his identity pushed aside by the “Enoch is right” signs held by members of the crowd. He whips them up and inspires them to violence with his Rivers of Blood speech, but the librettist uses nothing of the speech itself, rather paraphrasing it. Repugnant as he was, Powell was nothing if not an effective orator, and the reinterpretation of his words leaves them without the power they need to animate the crowd on the stage, and why? Why, when the words which really had that effect are available? Further evidence of the trite and nuance-free treatment of all these subjects is what follows. An injured working class man, whipped up by Powell and then hurt in the resulting melee, reports to hospital, and responds with the expected slurs and ignorance when the Indian doctors arrive to treat him. We find some humanity in the emotional struggle of the doctors in deciding whether to treat this man who sees them as less than him, but after he has been bandaged, the racist has an immediate Damascus road experience where he says, and I’m not making this up “I feel so much better already! You really are just like us! Come back to my house for jacket potatoes!”. If only it really was so easy. And for a final flourish, the doctors instead invite him home with them, where samosas and a further Bollywood dance number ensue.

Finale

We could not have dreamt what lay in store for us at the finale. Each of the themes has ended, though none has reached a resolution. The pilgrims have celebrated thanksgiving, the Cree women have been brushed aside by the pipeline builders, Pero’s fate is unknown as he hovers between suicide, escape or resignation, the Indian doctors are locked in a dance with their immediately converted racist, and the birds? Well, the birds are all dead, and thankful we were for it, but death is not as permanent as you might imagine in the world of Migrations.

The themes are not brought together in a way that weaves them or produces a satisfying message for the finale, but they are all flung onto the stage together. A song begins which seems intended to promote the brotherhood of all men and a future of working together for the good of all, but the language chosen is extraordinary. We are all mixed, we hear, because we all spread out from Africa. Both things are true, but absolutely separate from each other. Then it gets worse. No land is pure, the singers intone; no land is free from foreign feet. The extraordinary creation of this language of pollution and sullying in what is supposed to be a celebration of the wonder of diversity and family could not have felt more jarring. But the best is yet to come. Onto the stage come rainbow spacemen, resplendent in multi-hued pressure suits, and the song turns to further spreading out, from earth, to the stars, to Mars. The meaning of this is unclear; we have spent a whole evening unpacking the harms that humanity does to itself and the ruination of the earth through war and exploitation, and what? Are we lamenting the rush of exploitative consumptive capitalism into space? Or are we celebrating the ongoing spreading of this wonderful tapestry of humanity still further? The answer, like much else in this production, is obscured entirely. What we do see is people working with a fly harness on stage, and we expect that one of the miraculously revived birds is going to be flown as a final flourish, but no. What we get is a countdown, and the launch of a rocket. Let me be clear, this rocket is direct from Button Moon. It’s made of silver fabric, it unfolds from the floor, and it looks as though it came from the front my one of my friends’ childrens‘ pyjamas, apart from the size. CBeebies has returned at the very last, to sweep us into its panto.

The response of the audience was various. A number of people left during the performance, whether in disgust, in boredom, or for more prosaic reasons I can only hypothesise. After the break, I overhear a couple of people talking of being deeply emotionally affected, so maybe Migrations did hit its target for some people at least. But in the gents toilet, and on the way out, what I hear is a hum of dissatisfaction. It didn’t resolve or even engage with the issues, it was hard to listen to, these are some of the complaints. I agree, with both. It was an enormous and ambitious undertaking, with the intent to move opera forward, but it failed for me on every count. It was not musically enjoyable, lyrically poetic or moving, historically accurate, or emotionally satisfying, and it failed entirely to bring the narratives together in any meaningful way. I would warn you not to see it, but the run at the Mayflower Theatre is over. I think we can all give thanks for that.

Read the (more favourable) reviews of the other WNO operas performed at Mayflower Theatre this week:

Review: Welsh National Opera, The Makropulos Affair, Mayflower Theatre, Southampton November 2022

Photo: Craig Fuller

- In Common is not for profit. We rely on donations from readers to keep the site running. Could you help to support us for as little as 25p a week? Please help us to carry on offering independent grass roots media. Visit: https://www.patreon.com/incommonsoton