by Jackie Landman.

Claire Ballinger, Rose Wiles and Pauline Bisson were amongst the voluntary curators of new exhibition at SeaCity Museum, Southampton, Sugar, Politics and Money. They wrote about the exhibition for In Common and invited colleague Dr Jackie Landman, a visiting professor at the University of Southampton, to respond. This is what she wrote.

Not long ago, I discovered I had enslaved ancestors myself as well as by marriage. My great-great-great-grandmother Jana, b 1800, was an enslaved housemaid on a very large prosperous livestock farm near Graaff Reinet in South Africa, where I grew up. Slavery at the Cape is mostly overlooked and unlike in the Caribbean, Latin America and the USA, was largely domestic: very few estates had more than a handful of slaves. This year on 11th October, I celebrated the 200th anniversary of the birth of Jana’s eldest son, Africa (I have written about him below), who became my great-great-grand father. I lived and worked in the Caribbean for 14 years where I married a Jamaican. My husband’s grandmother Tulloch, born enslaved, lived in a homestead on the marginal land set aside for her enslaved parents to grow provisions. My son Machel Bogues was in the curatorial team responsible for the exhibition The British Slave Trade: Abolition, Parliament and People (2007).

So I saw the exhibition through the prism of family connections and my lived experience. I appreciated how it showed that slavery and the struggle against it touched ordinary lives in towns we do not normally associate with the slave trade or slave ownership or abolition. Yet, how intriguing that Bryan Edwards, who owned 6 Jamaican plantations and enslaved workers and wrote histories of the British Colonies in the 18th Century, died in the Polygon in 1800!

Claire, Rose and Pauline did very well to illuminate the lives of three women, an achievement considering how histories and archives are biased towards property owning wealthy, at a time when a married woman’s wealth was her husband’s.

I was perhaps most struck by the account of the formerly enslaved woman Zoe Loanda whose ordinary life was marvellous because she forged it for herself, secure in her humanity. Similarly I admire my great-great-grandfather, Africa Joel who became a wagonmaker, one of the few skilled occupations open to ‘Coloured’ (mixed) people in the Cape Colony in the 19th century. He acquired a small plot of land that he mortgaged thrice, a then common business practice, probably so three of his four offspring could become teachers, including Ellen my great-grandmother.

I thrilled to read about Ellen Craft’s courage and steadfastness as she ‘passed’ (for white) and cross-dressed as a gentleman (slaver) so she and husband William could escape from slavery in Georgia. It sparked memories: my mother’s aunt Anne had a green-eyed daughter Iris who passed: Aunt became Iris’s nanny so she could to be part of her grandchild’s life. Growing up in apartheid South Africa colour indicated race and encoded legal rights: where one could live, study, work, sit on the bus or cinema, who one could marry etc, with whites coming off best, ‘coloureds’ worse and blacks worst of all. In Jamaica in the aftermath of plantation slavery, there was residual customary not legal racism with a rich language of colour and status. I was told I was ‘red’ or ‘high-yellow’. I heard 19th terms for ‘mixed’ – the mulatto with a black and a white parent, a quadroon with one black grandparent and an octoroon for someone with one black great-grandparent, and then, the ‘one drop’ convention found in the USA.

Completely new to me were the delicate white lace bark cloth items on display from Jamaica. This craft practice was, brought from Africa, quite unlike the bark cloth of Ugandan royalty I’d seen in Kampala. I’m looking forward to finding out more about his and the many other ideas the exhibition sparked. I that the exhibition and Black History Month will prompt other black people to find out and share their stories.

- Top image: My grandfather Ellis and his sister Ada (both teachers) with my brother Robin as a small boy c1958. Robin was a teacher then went into FE and got an OBE. He is still active in a organisation dedicated to promoting equality and diversity in FE the Black Leadership Group.

____________________________________________________________________

Africa Joel 1822-1895: A great-great granddaughter pays a Bicentenary Tribute

by Jackie Landman.

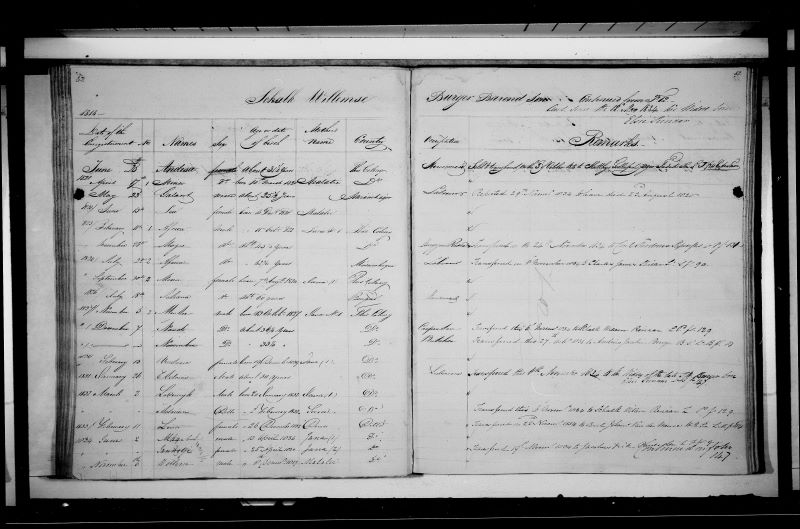

Africa Joel is the earliest ancestor whose place and date of birth, 10th October 1822, I know from the Slave Register for the Cape of Good Hope,1816 -1834. I celebrate him for himself and as an example of the many more Black, poor, marginalised and unfree ancestors usually left out of written history, dominated by accounts of and by white colonists and enslavers.

The archives provide a little information about Africa and his family. He was enslaved on Rhenosterfontein, a livestock farm near present-day Graaff Reinet, like his mother Jana. A housemaid, Jana had five children. Africa, the eldest, born on 10th October 1822, had three brothers, Mentor, Lodewyk and Maget and two sisters, Mina and Victorie. Jana and her children were among twenty-nine enslaved people on the farm, compared with 3-5 enslaved people per estate at the Cape in 1834.

The farm where Africa’s family lived was described by English polymath William J Burchell during his Travels in the Interior of South Africa in 1812. Burchell admired the well-built farmhouse, the numerous workshops, for wagon-making, carpentry, a smithy, and waterwheel driven mill for the largest sheep farm in the colony. Jana would have slept inside the farmhouse, so she and her young children would have met the travellers like Burchell who stayed there, in the absence of hotels.

When slavery legally ended on 1st December 1834, Jana and her children like all other “non-praedial slaves” in the British Empire aged 6 and older, became ‘apprentices’ for 4 years. Instead of being prepared for freedom and self-sufficiency, apprenticeship was actually a way to supply famers with labour. Freedom could only start when apprenticeship ended on 1st December 1838, when Africa was 16. Jana and Africa’s siblings disappear from the archives.

Africa became a wagon-maker, one of few crafts open to Coloured (“mixed”) people that commanded high wages and acquired his surname, Joёl, consistent with being a Christian. Africa married his first wife Clara on 6th January 1845 in Graaff Reinet Reformed Chapel. Clara died aged 31 leaving three young children, Jana, Jakob and Isaak, a modest 17-acre plot of land and belongings ‘of not much value’. Jana and Jakob ‘disappear’. Izaak (Crouch!) died young at his father’s house in 1882, an unmarried blacksmith.

Nurse Annie van Vuuren, ~ 31yrs, married Africa ~37yrs in the London Mission Chapel, Bethelsdorp. Unlike Africa, Annie was literate. She had four children, John, Peter, Louis and Ellen, my great-grandmother. Like many businessmen at the time, Africa mortgaged his land, presumably to help his children: Louis to pay fees to Lovedale Teacher Training College. He became headteacher at Graaff Reinet Independent Mission School. Ellen and Peter both became teachers too, as did Ellen’s eldest son Ellis, my grandpa, and my mother, Olive. I, my siblings Maeve and Robin and cousin Patti are the fourth generation of educators I know of in our extended Joel, Rosenberg and Landman families. Africa’s descendants live in South Africa, in England and in Canada.

We all surely also share with Africa the spirit, sense of personhood and humanity that enabled him to make and take opportunities, to strive and achieve for himself and his family.

- In Common is not for profit. We rely on donations from readers to keep the site running. Could you help to support us for as little as 25p a week? Please help us to carry on offering independent grass roots media. Visit: https://www.patreon.com/incommonsoton