by Sally Churchward.

Artist, poet, musician, father, husband, son and friend, Greg Gilbert died from cancer on Thursday. As a local journalist, Sally Churchward followed his career – from being the lead singer of Southampton indie band Delays through his being an emerging and then celebrated artist and poet, with numerous interviews in the city’s cafes over pots of tea. She looks back on his 44 years.

“I feel like a butterfly collector. I’m trying to pin those things down before they drift off, because everything’s changing so much.”

It was 2013 and Greg Gilbert was describing his incredibly detailed biro miniatures, drawn from family photographs, having just begun to exhibit them. The words were spoken more than three years before his cancer diagnosis, but they seem strangely prescient of what was to come and how he lived his life following diagnosis: leaving traces of himself, in songs, writing and art and in the people around him, striving to be present in the moment, with his partner Stacey, daughters, Dali and Bay, family and friends.

Now, it is those left behind who are the butterfly collectors, gathering and sharing their precious memories of Greg. He was loved – by those who knew him and by those who only knew his music or art, and there is a tangible need to pin down something of the magical sense of possibility he spread around himself in life. There is also something about butterflies that seem an appropriate metaphor for Greg – his metamorphosis over his career but also an air of magic and wonder, simultaneously concrete and a little other-worldly. Bright, beautiful, fragile.

Greg became famous first as a musician, the lyricist and lead singer with a haunting falsetto voice, with Delays, but he was always, always an artist. His earliest memory was of creating art.

“My first memory is of being 18 months old and showing my mum a picture of a bird I’d drawn,” he said.

“I’m not sure if I meant it to be a bird, or if I just scribbled and decided it looked like one. But drawing has been a constant in my life, a compulsion.”

After a childhood spent, at least in part, drawing, playing football (he was a talented player) and watching Box of Delights, Greg went on to attend Winchester School of Art, with the intention of becoming a conceptual designer for film. But with the success of Delays, art took a back seat, for a while, anyway.

Lost in a melody

Greg met future band mates Rowly and Colin Fox at school, with his younger brother Aaron completing the quartet, united, they said, in their love of Twin Peaks, The La’s, The Prisoner and Diego Maradonna.

First named Corky then Idoru, they released their debut EP in 2001, before releasing their first single as Delays in 2003, the timeless Nearer than Heaven, having signed to Rough Trade Records. They were hailed in the media at the time as being part of an emerging ‘Solentbeat’ music scene.

First named Corky then Idoru, they released their debut EP in 2001, before releasing their first single as Delays in 2003, the timeless Nearer than Heaven, having signed to Rough Trade Records. They were hailed in the media at the time as being part of an emerging ‘Solentbeat’ music scene.

Despite being a charismatic performer, Greg was reluctant to get up on stage, but knew that without doing so, the band would only ever be a hobby.

“I had to get on the stage out of necessity,” he said in 2013, at a time when he was feeling too anxious to perform. “I found it terrifying. I still do find it terrifying but I realised that when you get over that, it’s one of those things that you’ll be forever glad you did.”

The band’s debut album, Faded Seaside Glamour, broke the UK top 20 album charts and the boys from Bitterne Park were thrust into the spotlight. They found themselves dining with Elton John, supporting Manic Street Preachers and Franz Ferdinand, amongst others, touring worldwide, playing festivals, including the Isle of Wight, and appearing on Top of the Pops.

In total, they released four albums – Faded Seaside Glamour, You See Colours, Everything’s The Rush and Star Tiger, Star Ariel – the last of which Greg said drew heavily on Southampton and his experiences of living in the city. They had hits with singles including Hey Girl, Valentine, Lost in a Melody, Hooray and Hideaway, some of which made it into films and adverts.

As well as enjoying national and international success, the band had a strong fanbase in their home city of Southampton, regularly playing sold out gigs at The Joiners and The Brook, and enjoyed a loyal following.

When they began touring as a band, the conversation of moving away from Southampton came up, but for Greg the pull of his home city was always too strong and he continued to live in Bitterne Park, with he and Stacey making their home close to where he grew up.

“There was a certain amount of talk about getting away from the city but as soon as I did, I just missed it. Southampton is so important to me,” he said.

Just tell me the truth

At this time, Greg’s main focus was music but there were always other creative projects in the background. He wrote free verse, some of which he turned into Delays lyrics, and was always creating art. He designed and drew several of the band’s record sleeves, and began experimenting with biro drawings when on tour with Delays – the pens were to hand and he would pick them up and draw. He went on to develop his first signature style: incredibly detailed biro miniatures, drawn from old family photos and often collaged.

He was unsure about sharing his art with the world, but was encouraged to do so by his loved ones.

“The thing is, it’s easy to stay in your bedroom and tell yourself ‘I could have done this,’” he said. “It’s far riskier to put your self-image on the line and put yourself out there.

“I think without my family and Stacey pushing me, I could quite easily retreat and not interact much with the world.

“I almost compensate for that instinct with grand gestures, like the band and the art.”

Anxiety about performing was an issue at the time but Greg felt able, compelled even, to take his artwork out of his bedroom and share it with the world. The death of his much-loved grandfather was a particularly important catalyst in the decision. His grandfather always had a lot more time for Greg’s art than his music.

“It didn’t matter what I did with the band, every time I did a drawing and showed him, he’d say, ‘you’re wasting your life!’,” he said.

Also, at that time, two of his bandmates had recently become fathers and Greg and Stacey were expecting their first child, Dali, meaning the band had to take a break, and he could focus on his art.

Greg’s first exhibition, Requiem for a Village, was held in March 2013 at Harbour Lights Picture House in Southampton’s Ocean Village. It featured miniature biro and pencil drawings inspired by family photos and postcards from the 1970s, often focusing on background details. He loved the contrast to the digital age, where photos can be more easily planned and edited, and felt fascinated by the sense that these old family snapshots were capturing a genuine moment in time, and what he described as their honesty.

Greg said that the artists he most admired, such as Francis Bacon, Peter Doig and Richard Dad, developed highly idiosyncratic methods. That was his goal, “to find what’s most unmistakably ‘you’, no matter how different or obscure.”

Greg went on to have his art displayed in a number of galleries, and in his first year of going public with his art, won the Beaulieu Fine Arts Award. From the outset, he struggled somewhat with putting his work on display and in particular with selling it. It was a feeling that endured throughout his career – later on, in 2019, having shared his work on social media before A Gentle Shrug into Everything, his exhibition alongside Da Vinci at Southampton City Art Gallery, he had effectively sold all of his drawings before the opening night, but had to contact all of the would-be buyers to let them know that he couldn’t let the works go.

The narrative upended

Greg and Stacey went on to have a second daughter, Bay, and he continued to develop as an artist, but something wasn’t right. He had lost a great deal of weight and was plagued with stomach pains. In December 2016, he was diagnosed with bowel cancer which had spread to his lungs, in A&E. It was Bay’s first birthday. Greg was 39.

He later wrote about the experience in Blue Draped Cube, which featured in his poetry and prose anthology, Love Makes a Mess of Dying.

He detailed the surgeon telling him there was nothing to be done, the horror on Stacey’s face, his father’s anger, and him, from the distance in his mind into which he’d retreated, asking ‘How long have I got?’. He wrote about feeling what he described as the before-and-after-ness of the moment.

He and his family didn’t know how long he had, or if he would even live to see Christmas that year. Stacey spoke later of trying to think how she could acquire a copy of the then forthcoming Twin Peaks series, which Greg had been so looking forward to seeing, for fear he wouldn’t survive long enough to watch it. Instead, she threw herself into a fundraising campaign, fearing that the treatment Greg needed to save or at least prolong his life wouldn’t be available on the NHS (she was right, not all of it was), and launched the Give4Greg campaign, with the aim of raising £100,000.

It catapulted the couple into the spotlight. Their story was headline news and the donations came flooding in, becoming the fastest fundraiser to hit its target on the giving site and raising more than double the target amount. As well as personal donations, two fundraising gigs, Cavalry and Valentine, were organised locally by people keen to be active in helping someone so well-liked and now in such need.

It catapulted the couple into the spotlight. Their story was headline news and the donations came flooding in, becoming the fastest fundraiser to hit its target on the giving site and raising more than double the target amount. As well as personal donations, two fundraising gigs, Cavalry and Valentine, were organised locally by people keen to be active in helping someone so well-liked and now in such need.

Almost seven thousand people donated to the campaign, and Greg was as eternally grateful for the support as he was deeply taken aback by the response. He said afterwards that while he wasn’t comfortable with the attention, he recognised that it was Stacey’s coping mechanism. He didn’t expect anyone to donate to the campaign but wanted it to go well for her. The response shocked the couple, and wherever the subject came up, Greg always expressed his sense of gratitude and privilege at getting that level of support and practical, financial help. He would also always go on to express his anger that the NHS wasn’t being properly funded.

In a typical comment on the subject, he said: “I don’t think there is any excuse for the money not to be there for the treatments that people need.

“I think the money is there, and our government seems able to find it when they want to, but in the meantime, people are dying.”

Greg could talk for hours about politics. He was also deeply concerned about the effects of Brexit, particularly on the NHS, and frustrated at people not seeming to realise the implications for people like him, and for those without a fundraiser to fall back on.

“Few things anger me as much as people being glib about the effect that Brexit might have on things like essential drugs, and to see people so up in arms about something that clearly wasn’t impacting on their lives at all before the referendum,” he said in October, 2019. “I don’t think the EU is perfect but I don’t think it’s worth putting the NHS at risk for, according to the government’s own reports.”

Greg began a cycle of cancer treatment, much of which was extremely debilitating, and packing as much in to his well times, in terms of creativity and also family time – he and Stacey loved getting away for a night or two at their favourite hotel, The Pig in the New Forest. This was also the location of their wedding celebrations. The couple married in August 2018 at a small ceremony at Southampton’s Westgate Hall. They had been together for 12 years at the time, and got engaged in 2014, but Greg had been too ill for them to wed. They joked after his diagnosis about balancing wanting to wed with not wanting it to be ‘the panic wedding’.

We’ll put the law behind us

Greg’s diagnosis was a huge turning point, but the changes were not all negative. It spurred him onto great creativity and mindfulness, freeing him of the weight of expectations from his previous creative endeavours and allowing, even compelling, him to find new ways to express himself. He said that the diagnosis had changed him in ways that he’d wanted to change, but had struggled with and that he wouldn’t want to go back to how he was before.

“Being diagnosed was like the ultimate exposure therapy – it smashed through everything in one moment,” he said in a treatment break in the summer following his diagnosis.

“It was like someone cleared away all the clutter. Everything is heightened.”

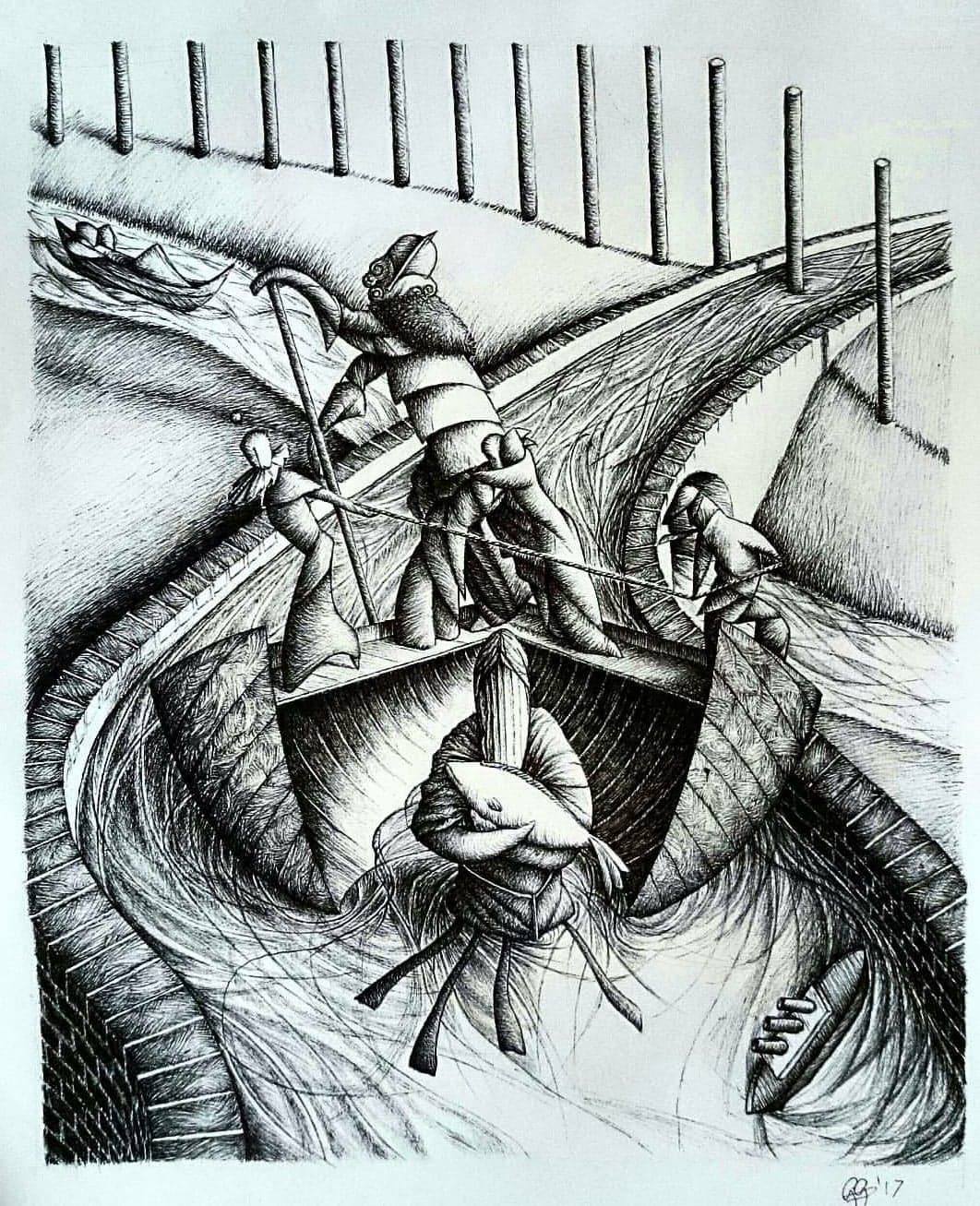

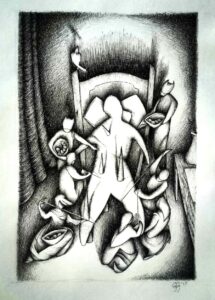

Greg had wanted to move away from producing the biro miniatures, which were time consuming and physically draining, being bent over for hours working on tiny details. After his diagnosis, he began producing sculptural drawings, before moving onto his convalescent drawings and abstract paintings. He had always wanted to paint, and had produced some work such as Earl, a huge version of which was put on display in Southampton city centre in 2016. But prior to his diagnosis, he felt constrained by being known for his biro miniatures.

Greg had wanted to move away from producing the biro miniatures, which were time consuming and physically draining, being bent over for hours working on tiny details. After his diagnosis, he began producing sculptural drawings, before moving onto his convalescent drawings and abstract paintings. He had always wanted to paint, and had produced some work such as Earl, a huge version of which was put on display in Southampton city centre in 2016. But prior to his diagnosis, he felt constrained by being known for his biro miniatures.

He began to plough through philosophy books – a pile of which Greg regularly carried round with him to delve into when he stationed himself in coffee shops, such as Waterstones in Westquay shopping centre and Trago Lounge in Portswood. His reading influenced both his art and the poetry that he had been writing privately for some years. He said he had turned to philosophy both to help find his way through what life was throwing at him and as direct fuel for his work.

Greg carried notebooks with him, to cafes, to chemotherapy, and artwork and words poured out of him into them. He didn’t set out with a plan in mind of the finished piece, but would draw images that came from deep inside him, and which, at the time of creation, he often didn’t fully understand.

“I have notebooks full of drawings and have had ever since I was diagnosed,” He said in October 2019. “I just want to get them onto paper. The images feel precious, like I’ve found little jewels of self that I’ve been looking for. I start putting them down when they come without trying to make an image. I feel almost as if I want to give birth to them. Lots of the imagery is quite explicit in terms of what it conveys after the fact, but I’m not aware of it when I’m doing it.”

It wasn’t only in his artistic endeavours that Greg felt a positive change following the horror of diagnosis. It was also in the way he lived, day to day. Living in and appreciating the moment became a necessity, and while he and Stacey had always meditated it took on new importance in their lives. Greg said that he was a far more positive person than he had realised and felt gratitude for all the things there were to be grateful for, which he chose to focus on.

Greg found that the sense of the limits on time had been transformational. “We’ve been made so acutely aware of transience, so you become more aware of when you’re messing about or drifting along,” he explained.

“It feels like the only thing that has any worth are the absolute truths. There’s no time to swerve and express platitudes – what’s the point?”

Greg went on to combine meditation with his art, using it to interact with his drawings in his mind, and forge new connections between his conscious and subconscious.

“I’ve been going a step further into the images,” he said. “I’ve been having discussions with the characters I’ve drawn. It’s fascinating.”

For Greg, while he was not without cynicism, particularly about politics, there was no place for irony or cynicism in art. He said that in the work of the artists he most admired, such as Paul Nash and Stanley Spencer, you could feel that they had experienced or witnessed suffering, and transformed it into something beautiful. That sense of honesty that fascinated him about old family photographs, and which he focused on in his early miniatures continued into his later work and, indeed, his personality. There was a sense that if it wasn’t honest, it wasn’t worth expressing, in any form.

“I haven’t got any room for cynicism in art,” he said. “For me it needs to be sincere.”

There are no secrets here

A number of Greg’s convalescent drawings, as well as abstract paintings, were part of A Gentle Shrug into Everything, his exhibition alongside the work of Leonardo Da Vinci at Southampton City Art Gallery in early 2019. An anthology of his poetry, Love Makes a Mess of Dying, was published to coincide with the exhibition, after he was chosen as one of four Laureate’s Choice poets by Carol Ann Duffy.

Greg began writing poetry at around the same time as he started to show his art. Always an avid reader, it was whilst reading some of his favourite writers such as Sylvia Plath and Walt Whitman that he realised he enjoyed the language as much as the narrative and became drawn to poetry.

“Artistically, I have always been very visually preoccupied, but then I saw beauty in poetry equal to any painting,” he explained.

Greg had some pieces of poetry published in an anthology and decided to explore the Southampton poetry scene. He was writing because he felt compelled to do so, but was very self-conscious about it, so he went to a poetry night to “scare myself into sharing my work.”

Greg had some pieces of poetry published in an anthology and decided to explore the Southampton poetry scene. He was writing because he felt compelled to do so, but was very self-conscious about it, so he went to a poetry night to “scare myself into sharing my work.”

At a reading at The Brook in Southampton, he met Gillian Clarke, the former National Poet of Wales, who felt that what Greg was saying about his illness was important and should be published. Without mentioning it to him, she passed on some of Greg’s work to Poet Laureate Carole Ann Duffy. Out of the blue, Greg had an email from Duffy, saying she was interested in seeing more of his work, with the possibility of him being the author of one of the four ‘Laureate’s Choice’ publications she was involved in annually.

Greg said he thought: “‘Hold on a minute, this is pretty much everything I ever wanted for my poetry,’ I had intense imposter syndrome.”

Shortly ahead of the publication, Greg said that the poetry was so raw, and brutal in terms of his honesty about his own fears, that he didn’t really want his family to read it. He felt the need to balance the possible impact on his loved ones with his need for expression, and found he “had to jump off a cliff with it.”

He added: “If I’m not being raw, honest and scared, it’s probably not worth publishing.”

Greg said that he had to write and create art for himself, to express how he was feeling. After his diagnosis he didn’t pursue gallery shows or sales of of his work, keeping much of it or giving it to his family. He had to create because it was who he was. Art had always been there. It had helped him through the death of his grandfather and it helped him through living with cancer, even when he knew he only had a matter of weeks to live.

“That’s been my biggest coping mechanism throughout this, through my whole life.”

Our last night on Earth is for living

When Greg announced on social media on August 8 this year that he had been taken off cancer treatment, and was being treated solely for pain, at the Countess Mountbatten Hospice, he neatly summed up what was most important in his life: first and foremost his family and his art. He added gratitude for his family, friends and supporters, and, characteristically, threw in a mention of politics.

He wrote: “I’m trying to get home for a couple of hours a day to see the kids, energy willing, and hope I can still find the time to create. I’m impossibly lucky to have the family and friends I have, as well as all the considerate souls out in cyberspace who regularly beam me their good vibes. I still believe in magic, the power of a good gesture and laughter. I want to fill the days ahead with all of these and so much more. No doubt my social media will return to its usual blend of drawing/painting/music/ranting about tories/Batman and cute animals. In the meantime I’m sending lots of love and thanks to you all xxx” .

Indeed, he was true to his word. Greg continued producing art for as long as he was able to, sharing the stunning ink on paper The Face of God, just over a week later, having completed it in the hospice “through a foggy mind”. Greg also managed to go home to spend time with his family, taking some quiet time out to draw with his daughters and drink tea with Stacey, and eventually was discharged to his parent’s home, where he passed away on September 30. And Greg was true to his word about political comments too – in his final Tweet, written on September 1, he said: “Even in my ragged condition I’d still pay extra to help the poorest. Our country is f**ked by unprecedented greed and selfishness.” (stars added).

Indeed, he was true to his word. Greg continued producing art for as long as he was able to, sharing the stunning ink on paper The Face of God, just over a week later, having completed it in the hospice “through a foggy mind”. Greg also managed to go home to spend time with his family, taking some quiet time out to draw with his daughters and drink tea with Stacey, and eventually was discharged to his parent’s home, where he passed away on September 30. And Greg was true to his word about political comments too – in his final Tweet, written on September 1, he said: “Even in my ragged condition I’d still pay extra to help the poorest. Our country is f**ked by unprecedented greed and selfishness.” (stars added).

Greg said in his heartbreaking announcement of August 8 that he ‘still believed in magic’ and there was a magical quality to his life and work. Many of those who have paid tribute to him have mentioned it, and it was a recurring theme for him – not necessarily quite a belief in the supernatural but an openness to it; a curiosity as to what possibilities might lay slightly out of reach, a sense of wonder at what could be hidden in the everyday. Magic in the seemingly mundane.

For many of his family, friends, fans and followers on social media, there was a sense that he was almost a bridge to that childlike wonder, and a feeling of some of that magic brushing off, the gift of being shown the world the way Greg saw it. Perhaps it was simply that as well as being talented, humble and kind, Greg really paid attention to the world around him and the people in it, striving always for honesty, and that, in itself, was magical.

“As a kid, I was fascinated by things like alleyways and edges to walls,” he said. “I can remember getting butterflies from that sense of liminal space and passing from one space to another. There was a thrill of magic at simple things. I can still feel like that, especially in nature.

“I often feel like I’m only just around the corner from finding out things.”

- All photos previously supplied by Greg Gilbert, with permission for them to be used alongside stories.

A personal note: As a journalist on the Southern Daily Echo, and then In Common, I followed Greg and his career, from when Delays were an exciting new local band, through him first showing his art, and beyond. I went to too many Delays gigs to count, but it was in early 2013, when he first showed his biro paintings, that I sat down to my first pot of tea and lengthy chat with him, for what became a regular pattern of interviews that segued into conversations about politics, family life, childhood memories, reading recommendations and more, with notepads and deadlines long forgotten. He went from being a contact to a friend. I have drawn on my interviews for The Echo and In Common, and our chats as friends for this tribute, to a person whose range and depth of talent might have been annoying if he wasn’t such a nice bloke, and my friend.

A personal note: As a journalist on the Southern Daily Echo, and then In Common, I followed Greg and his career, from when Delays were an exciting new local band, through him first showing his art, and beyond. I went to too many Delays gigs to count, but it was in early 2013, when he first showed his biro paintings, that I sat down to my first pot of tea and lengthy chat with him, for what became a regular pattern of interviews that segued into conversations about politics, family life, childhood memories, reading recommendations and more, with notepads and deadlines long forgotten. He went from being a contact to a friend. I have drawn on my interviews for The Echo and In Common, and our chats as friends for this tribute, to a person whose range and depth of talent might have been annoying if he wasn’t such a nice bloke, and my friend.

- Could you help to support In Common, for as little as £1 a month? Please help us to keep on sharing stories that matter with a monthly donation. Visit: https://www.patreon.com/incommonsoton