By Benn Orgill.

The badness. It’s on the move. It was a long winter – prices rising, plagues lingering, peace talks floundering. And what’s to be done as we watch disaster strike from near and far? Try again, fail again, fail better, as Samuel Beckett would have it. And he’s not the only one. As one of the most influential dramatists of the 20th century, Beckett is part of a lineage of Irish literary genius that speaks directly to our yearning for meaning and purpose in the noise of Being.

If this all sounds a bit serious, it’s because it is, but far from dour gloom mongering, one of the essential qualities of Irish literature is humour – pithy, imaginative, and rebellious. We can gesture here to ‘gift of the gab’, the craic, James Joyce’s exalted stream of consciousness, but while lyrical dexterity is a national trait, the function it serves reveals more about Irishness than mellifluous phrasing alone.

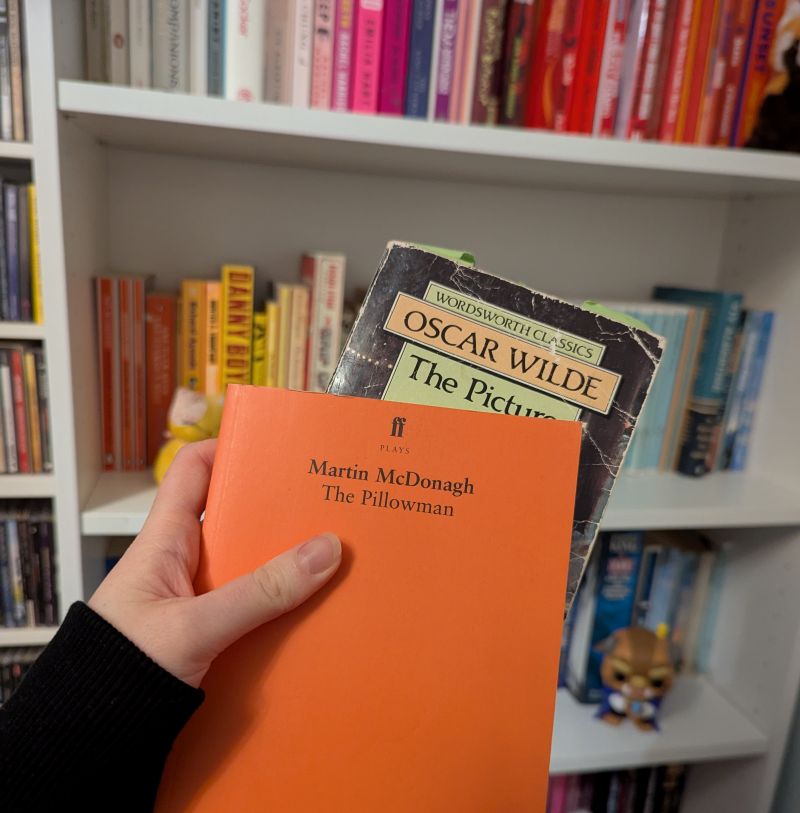

As a member of the upper classes and early queer icon, Oscar Wilde lacerated repressive Victorian high society with scandalous aphorisms and asserted that if we are to have purpose in life, it is in devotion to beauty. All the best lines in The Picture of Dorian Gray are reserved for the caustic, decadent aristocrat Lord Henry, who satirises manners, social responsibility, and conventional virtues in a book that is ultimately a warning against the nascent narcissism of image-based culture. Beneath the barbs and affected aristocratic recklessness, Wilde is concerned with the soul of humanity, the limits of pleasure before it turns malignant, and the need for self expression regardless of – and often in opposition to – notions of any prevailing authority.

Later, Samuel Beckett cured nihilism and isolation into starkly life affirming absurdism, answering the 20th century’s neurotic grappling for sense and stability in the aftermath of world war (Beckett served the French resistance). In Endgame (Marvel be damned), Beckett personifies depression and anxiety in the characters Hamm and Clov – one unable to stand up, the other unable to sit down – co-dependent and constantly in conflict, their provocations and humiliations an engine for survival in banal, unchanging hopelessness. We might recognise their bickering from inside our own heads, and laugh in relief that we aren’t alone in our existential angst. Alain de Botton recently pointed to the pessimist philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer’s quote that ‘Today it is bad, and day by day it will get worse―until at last the worst of all arrives’ as a great example of dark humour, offering us relief in the recognition of our predicaments and gratitude for what we have now. So it is with Beckett.

As it is with the playwright and director Martin McDonagh, who you will know most recently from Banshees of Inisheerin, but also In Bruges, Seven Psychopaths, and Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri. For a long time, McDonagh’s reputation rested on controversy, partly generated by scripts full of violence – linguistic and otherwise – that operate entirely outside of political correctness. However, these stories of witty, amoral characters lull audiences into a false sense of security before ambushing them with moral quandary (can gangsters be led to redemption?) and spiritual discovery (what happens when a psychopath bends their tendencies towards love and sacrifice?).

At face value, In Bruges – a pulp fiction take on Beckett’s Waiting For Godot – is about the exploits of Ray (Colin Farrell) and Ken (Brendan Gleeson), two hit men laying low in Belgium while awaiting further instruction from their boss Harry (Ralph Fiennes). Ray is plagued with a guilty conscience after a job went wrong, eventually driving him to suicidal intent around the same time Ken learns that Harry’s further instruction is to kill Ray. There are plenty of brutally funny lines and violent slapstick that people like to quote, but beneath the surface, the film is a parable about the value of life and the possibility of redemption. Standing between Harry’s designs on Ray, and Ray’s designs on himself, Ken insists on a measure of mercy so that Ray has a chance to make something of his life. It is new testament sentiment with postmodern grit, recalibrated for an audience jaded by irony and sensationalism, making the case that whatever law or misery compels us, grace and redemption are real and possible as an alternative to letting violence beget violence.

The idea of being your own moral authority tracks through Seven Psychopaths, most successfully in the character of Christopher Walken’s Hans, a Quaker with a vengeful streak. When gangsters attempt to intimidate his friend, Hans instructs him to ‘have some pride in yourself, have some faith in Jesus Christ as your lord and don’t tell [these people] a thing’. Later, when a gangster points a gun at him and tells him to raise his hands, he asks ‘Why?’. He will not give in to petty tyranny as he is reconciled to the world in its viciousness (as illustrated in his backstory) and acts as the model for convictions – old testament, new testament, and Buddhist. One of the more poignant messages of the film comes in the form of Hans riffing on the story of Thích Quảng Đức, a monk who self-immolated in protest of the Vietnam war. Hans imagines a fellow monk pleading with Thích to desist as it won’t help the cause. Thích Quảng Đức responds ‘It might’ and commits the act: a powerful example of sacrifice and rebellion against oppression. It is an extreme example too, but we should accept it in the spirit that it’s given – our acts of resistance may be doomed to fail against a formidable enemy and world in crisis, but in our dissent, we keep the possibility of a better world alive. Try again, fail again, fail better.

Whilst I don’t have time to really get into it, I must briefly mention Martin McDonagh’s brother John McDonagh, whose film Calvary is a bracing articulation of faith and integrity in stewardship of neglected souls, commanded by the infinite sympathy of Brendan Gleeson’s face in the guise of a Catholic priest. It is a study of a man beneath the vestments, his genuine concern for people, the sad realities of their self-destructive habits, and his community. It is morally complex and nobody comes out of it clean (not least the Catholic church), but it turns both heart and mind to considerations of how alienation is a corrupting force, and that our responsibility for ourselves and accountability to each other is the broadest church and the one true faith.

For a nation that has suffered English oppression, enforced starvation, civil strife, and mass exodus, Irish literature is rebellion and it is consolation, naming the darkness and laughing at it, keeping the faith that a better world is possible. This St Patrick’s Day, we can take on these lessons to navigate the trouble ahead and have a laugh whilst we’re at it.

- In Common is not for profit. We rely on donations from readers to keep the site running. Could you help to support us for as little as 25p a week? Please help us to carry on offering independent grass roots media. Visit: https://www.patreon.com/incommonsoton