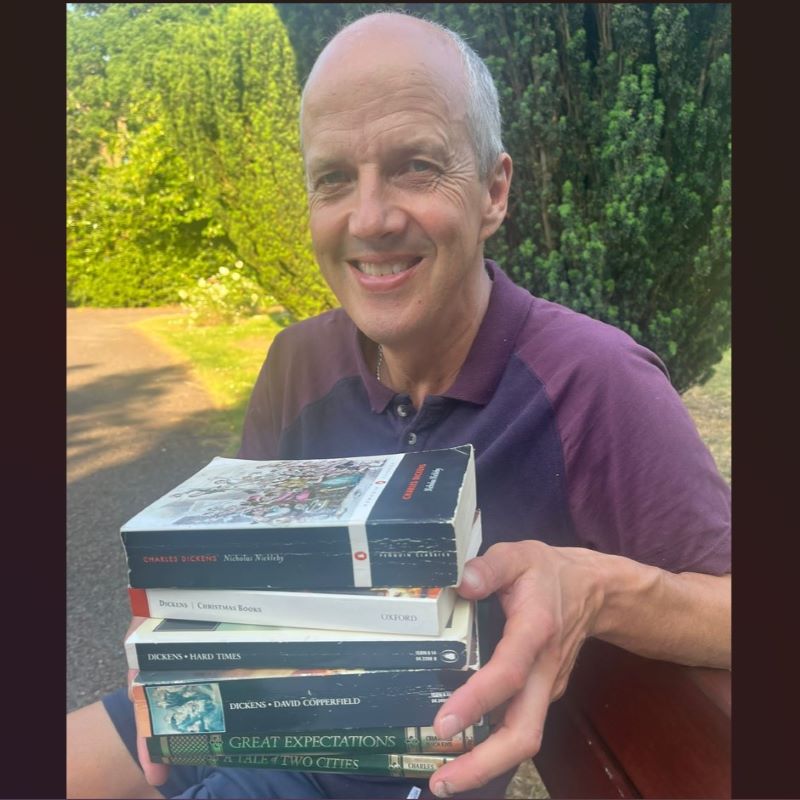

Which Charles Dickens novel is your favourite? That’s the question which set In Common writer Nick Mabey on a two-year reading mission. Finding himself unable to answer because he hadn’t read any Dickens, Nick became aware of this gap in his literary knowledge and resolved there and then to put things right. But he didn’t just read one of Dicken’s stories – he read all of them, one after the other.

Here he tells Under the Covers about his experience of getting to know the works of this influential Victorian author…….

*****

by Nick Mabey.

Charles Dickens is one of the UK’s most famous authors, perhaps second only in terms of popularity to the Bard himself, Shakespeare. So, when I was asked which of his works was my favourite, it was with great embarrassment and not a little shame that I had to admit to having read none of his books. As I’m a prolific reader, my answer was as much as surprise to me as it was my questioner. Thus began my great Dickens adventure.

That day I committed publicly to reading all of Dickens works, in the order they were written. It was probably an over-reaction to the humiliation I had experienced at this giant hole in my literary experience, but at least it acted as a spur toward action. Summoning the great modern oracle that is Wikipedia I immediately decided to discount the novellas and short stories (apart from A Christmas Carol, which was too famous to ignore). I also chose to omit the Mystery of Edwin Drood on account of Dickens not getting round to finishing it before dying. This left me with a grand total of fifteen books – I was off and running!

If you are contemplating the same journey I went on let me give you the warning I would have appreciated. Pickwick Papers is his first novel and probably the hardest to read. The plot meandered; the style evolved; it was like I was witnessing the emergence of the writer’s craft through the pages of his first effort. It was useful to learn that Pickwick Papers, like many subsequent stories, was published in periodic instalments rather than as a complete book. It certainly felt like he was making it up as he went along, something I believe he later admitted.

The writing apprenticeship did not last long and bore immediate fruit with Oliver Twist, which was a great read. The story I grew up with – based on the 1968 musical Oliver! – occupies only the first half of the book, after which there is much time spent with characters we know so well. Next up, Nicholas Nickleby, one of several titles I thought I knew but soon realised I barely understood. For me this was a masterpiece, and I can only imagine how it was received at the time – 1838. For a story like this to be published in monthly instalments must have been tantalising for readers and created quite a froth on the streets of London. Dickens cleverly set most of his stories contemporaneously in the streets of London, where his audience lived, and the impact on popular culture must have been huge.

I read the books pretty much back to back, allowing a few days after completing one before embarking on the next. Most were engaging page turners, and only a couple proved harder work (I’m thinking of you Martin Chuzzlewit). I’m often asked which is my favourite and instinctively I say Bleak House (plot spoiler – it’s not a bleak house). I’m not sure why, partly I guess because I didn’t know the story at all, whereas most others were weighed down with expectation. And partly because of our heroine, Esther Summerson, who is a particularly well-drawn, triumph-over-adversity character so well known in Dickensian literature. It’s tough to pick a favourite though. There are so many classic tales. A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations provide a fitting climax to the series, with Our Mutual Friend a complicated, curious postscript.

It took me a little over two years to complete my quest. As I look back I realise how extraordinary was the mind of the man who wrote this collection. Dickens’ books are filled with the most colourful characters, whose names alone are works of comic art. Rogue Riderhood, Mr. and Mrs. Spottletoe, Wackford Squeers and Lord Lancaster Stiltstalking are just a few of the hundreds of treasures to be found in the writing.

More striking than the colour though, is the darkness in much of Dickens’ writing. I was surprised at his barely disguised political critique of Victorian society. Famously inspired by Dicken’s own life, and particularly that of his father, socialist ideology is writ large through pretty much every story. For all the comic overtones, the narrative is often heart-wrenching or anger-inducing.

I’m left with a deep gratitude for the conversation that led to my taking on this challenge. I thought I knew Oliver Twist, David Copperfield, Nicholas Nickleby, and Pip Pirrip, but I really didn’t. We’re lucky to have had Charles Dickens, both as a wonderful creative force and as a vivid chronicler of Victorian society.

- In Common is not for profit. We rely on donations from readers to keep the site running. Could you help to support us for as little as 25p a week? Please help us to carry on offering independent grass roots media. Visit: https://www.patreon.com/incommonsoton

You may also like: