By Laura McCarthy.

To mark International Women’s Day on March 8th, we take a look at the great women of horror writing.

Stephen King may be known as the ‘King of Horror’ but to decide on a Queen poses too much of a challenge, as there are just too many worthy of the title. This International Women’s Day, it is our duty to bow down to these matriarchs of murder and misery.

Mary Shelley (or, as I like to call her, Mary Queen of Rot) was an innovator of the genre, writing Frankenstein at the enviable age of 18. Shelley is a formidable example of how to implement the uncanny to truly terrify; her original character is not so much the rectangular-headed monster from 1931 but an incongruous blend of beauty and the grotesque. The creature’s ‘lustrous’ black hair and pearly teeth provide a stark contrast to the deathly ‘yellow’ skin, the juxtaposition of these features heightening the horror. Doctor Frankenstein uses carefully selected features from corpses, chosen with the intention of making the perfect creation, but his transgression is too great. His creation could never be perfect when made through blasphemous methods.

Another beloved great is Shirley Jackson, well known for The Haunting of Hill House and We Have Always Lived in the Castle (the latter being one of my personal favourites). For me, having recently finished her novel The Sundial, it has been surprising to see how little it is discussed in comparison. Jackson’s usual use of Gothic characteristics and sense of impending doom is as relevant here as ever. However, the writing stands out from her body of work for the pure hilarity. Of course, glimmers of dark humour can be found in her other novels but it really shines through here. From the very first page, we are gifted with this brilliant exchange between mother and daughter:

‘Fancy, dear, would you like to see Granny drop dead on the doorstep?’

‘Yes, mother.’

And, later, we see the aforementioned grandmother insist on wearing a crown to dinner with the coming of the apocalypse to much comedic effect.

Many who dislike the novel cite the repellent cast of characters as one of their main critiques but, in my view, we were never meant to like them, we were only meant to laugh at them. The fact that they’re two dimensional archetypes is the whole point. It reads as a satire, critiquing the entitlement of the upper-classes.

These wealthy clowns continually display their ridiculousness and the titular sundial serves as a motif which reflects their ignorance. A sundial can approximate the time during daylight but cannot offer any insight at all after the sun goes down; the characters have only a vague idea what the world is really like. As such, I personally think that the apocalypse they are so certain will arrive is not going to come. After all, their belief is based on mere hallucinations.

What is not a hallucination or illusion is the greatness of Daphne du Maurier. Anyone who knows me knows that she is my favourite author of all time. In fact, a book club I was part of became quite tired of my repeated recommendations and you might think that would stop me from praising her again now… but it won’t.

Du Maurier’s Gothic masterpiece Rebecca is certainly her most famous novel. In this, the setting becomes a character of its own, even more so than our protagonist, for Manderley estate has a commanding presence throughout whilst our narrator remains unnamed, like she is without a sense of self (an idea which continues through the narrative as she constantly feels in the shadow of the last Mrs de Winter). The famous opening may be the most exquisite descriptive writing in the history of literature. At the start, the property and gardens are the first thing we see through the narrator’s recollection of a recent dream, and so Manderley immediately asserts itself, almost as if it were the main character. We are not yet aware that the house has burned down at this point, but the fact that the narrator still dreams of the estate highlights the enduring presence of such a place. Du Maurier personifies the setting, solidifying Manderley’s identify by giving it a sense of power and an aura of mystery. If you’ve never read this, stop depriving yourself and find a copy immediately.

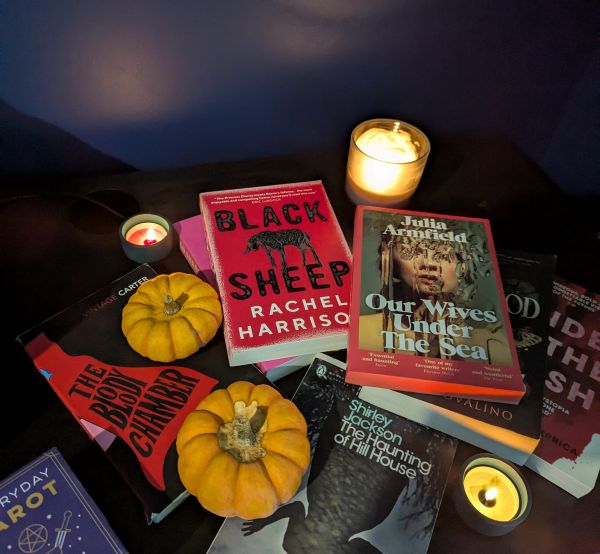

Whilst I have mainly discussed some classics here, we cannot forget that we have so many amazing modern writers of diverse backgrounds – women who are transgender, people of colour, disabled – who are writing wonders of horror. Gretchen Felker-Martin has a vivid and intense style, Oyinkan Braithwaite’s My Sister the Serial Killer exemplifies her skill for crafting compelling thriller narratives, and Alison Stine represents the deaf community in her dystopian work. It’s a joy to see women succeeding in the genre. Rachel Harrison has been on a roll, putting out a consistent stream of engaging horror novels which usually centre women. Such authors are even taking inspiration from other renowned women, as seen in Tori Bovalino’s blood soaked novel Not Good for Maidens which expands upon Christina Rossetti’s poem Goblin Market. And the list goes on but I have to stop somewhere. In short, it’s never been a better time to be a woman who loves horror.

- In Common is not for profit. We rely on donations from readers to keep the site running. Could you help to support us for as little as 25p a week? Please help us to carry on offering independent grass roots media. Visit: https://www.patreon.com/incommonsoton