By Laura McCarthy.

It is a well known fact that George Orwell’s dystopian novel 1984 is the most banned book of all time. The irony of censoring literature which is prophetic of extreme censorship isn’t lost on most of us. You may well have heard of other past bans too, including that of Lady Chatterley’s Lover in the late 1920s for supposedly immoral and inappropriate content. If these folks from the 20s were to see how popular steamy books like Icebreaker are in the modern day, they would be less than impressed – great Caesar’s ghost!

This is not a problem of the past, however. In fact, the American Library Association found that in 2023 there was a 92% increase in titles targeted for censorship compared to the previous year. Although incidents in the UK are comparatively much lower than in the US, it is still an issue here. Last year, research conducted by the Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals found that one third of librarians had been asked to censor or remove books and that this amount had risen from previous years. Most worryingly, targeted books tended to focus on race, empire, and LGBTQ+ themes.

The boycotting and banning of books is inherently political, regardless of which end of the scale that may be or the magnitude of the action taken. From Sally Rooney’s boycott of Israeli cultural institutions to the other extremity of Nazi book burnings, the intentions behind such actions can vary massively and yet still remain wholly political.

When politics boils over into outright hatred, prejudice can emerge in more destructive ways than just a request to remove a book. In attempting to silence minority voices, those angered may take matters into their own hands. In Cork last year, protestors tore up LGBT books due to the belief that such themes were unsuitable for young adults. Similarly, in 2022, teachers at a Catholic school in London cancelled a talk by gay author Simon James Green as his books apparently ‘fell outside the scope of what is permissible in a Catholic school’.

Suppressing the voices of authors, especially minorities, is arguably morally wrong but, more than this, it may even be antithetical to the aims of those banning literature. Think about it. Perhaps, if you make a big enough fuss about something, you might actually draw more attention to it than if you’d just stayed quiet. And if your goal is to censor a text to stop people from reading it, you’re much more likely to achieve the opposite, as humans are naturally curious lovers-of-gossip and will want to see what is so objectionable about it.

This leads me into discussing one of my most recent reads. In December, I read Stephen King’s Rage, initially written under the pen name Richard Bachman. For those not in the know, King adopted the pseudonym in the 1970s because publishers couldn’t keep up with the sheer amount he was producing and didn’t want to oversaturate the market with the King brand. It was also somewhat of an experiment for Stephen King in which he could test a question he had about his writing: did readers buy his books due to his work or his name? Was his fame due to talent or luck? However, he never really got to properly test the theory, as his alter ego of Richard Bachman was quite quickly discovered in 1985.

Rage was ‘Bachman’s’ first novel. It is a thriller about a school shooter… so maybe you can already predict where this is going. In the novel, we follow Charlie Decker as he fatally shoots a teacher and proceeds to spontaneously turn his class into a toxic psychotherapy group. In the 80s and 90s, after Bachman had been revealed to be King, Rage was associated with a few real school shootings. In 1991, one student held his maths class hostage in a similar manner to Decker. Luckily, in this case, no one was harmed but this cannot be said of all the incidents, as seen in 1997 when another student shot eight of his peers; the shooter had a copy of Rage in his locker which initiated King to take it out of print.

How many times have we seen different forms of media being blamed for real world crimes? Whether it’s Quentin Tarantino films or the video games Manhunt and Hatred, many works have come under fire (pun intended) for inspiring violence. If anything, the anger towards such media attracts more attention to these works. I, for one, hardly play computer games and yet I am fully aware of the existence of both Manhunt and Hatred, despite the fact that they are mediocre games from a decade ago.

I think the same rule applies to Rage. Before Bachman’s identity had been revealed, it was an underground favourite, not attached to any real violence. It was only after the book was linked to the incredibly famous Stephen King, that crimes were linked to the novel. In general, if more eyes are on something, it means that more unstable people are also likely to see it – that’s simple statistics in action. Moreover, when someone is not doing well mentally, they may not need a significant incentive to commit unsafe actions. For example, within the past year, streamer Justfoxii allegedly had her car set on fire by a stalker, who was a viewer of hers, due to the fact that he felt ‘jilted and scammed’ by her since she had a boyfriend. We cannot blame this streamer, just like we cannot blame Stephen King, for the disproportionate acts of violence inflicted by another.

Now that Rage is out of circulation, the intrigue is only heightened. I know this because it is exactly why I read it in the first place! What is most ridiculous about this is that the book is certainly one of King’s worst. This shouldn’t be surprising if you know that he wrote the original draft when he was a high school student. It reads as rather amateur and clumsy. Despite the short length, living in the head of the insufferable main character is a tedious experience and I have found that queer readings of the text online are actually more interesting than the intended substance. Such a fuss over this? Really?

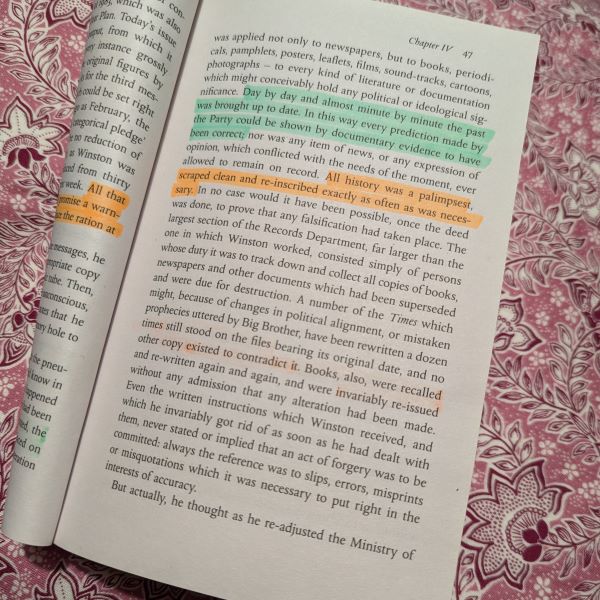

To conclude, for some, censorship of literature may seem a worrying symptom of dystopian society. In 1984, everything is censored and edited, to the point that even history is altered. In Fahrenheit 451, books are outlawed and burnt. Across dystopian texts, those who challenge the established status quo are silenced. Some are already feeling stuck in the bleak version of the world which such texts envision. For example, back in April, a series of public order laws made many question whether the freedom to protest and, by extension, the freedom to express views and opinions was starting to become threatened. Returning to the case in hand though, you may be concerned that normalising the censorship of texts sets a troubling precedent for more extreme silencing like that we see in Orwell’s work. Whilst it is only fiction right now, it could be the catalyst for an ever increasing problem.

My take? Censorship of literature is a fool’s quest. As I have previously mentioned, it simply serves to grow the interest of many – the exact opposite of the intended outcome. So, why bother? For the rabid mob trying to rip up library books, you only serve to make yourself angry and look a right joke to everyone else. With equality hiring laws in place, if you’re photographed in a hateful attack against minorities, burning books as though you’re in Germany in 1933, it may also be a quick way to lose your job. That said, when we start seeing more invasive censorship led by the government, like that of Thatcher’s Section 28 where books seen to be ‘promoting homosexuality’ were banned in schools and libraries, we should be worried. I hope, perhaps naively, that that will not happen in the UK.

- In Common is not for profit. We rely on donations from readers to keep the site running. Could you help to support us for as little as 25p a week? Please help us to carry on offering independent grass roots media. Visit: https://www.patreon.com/incommonsoton