The first sign that something is about to happen is the drone of the helicopters. Four fly over towards the mountain and then circle down the slope behind the trees. A car appears up the hill and around the bend towards us, its loudspeaker yelling “Huit minutes, huit minutes !” before accelerating off beyond the crowd on the green, through the narrowing stretch between farm buildings. It slows to take the right-angle corner and disappears out of sight. Minutes later it is followed by a police vehicle, it’s intermittent, unmistakably French siren ramping up the atmosphere.

I’ve watched the Tour de France for years, a regular afternoon or evening appointment with the TV, often perched on the edge of the sofa as the drama of one of the many different but inter-linked races within the Tour unfolds daily for three weeks every summer. This year we went to France to catch some stages. Nothing on TV prepared me for the real thing – watching the Tour in the high Alpes.

From the valley road our rented Fiat 500 struggles up to the village of Le Noyer. We park in a field amongst cars and campervans, immediately bumping into one of the perennial roadside ‘Tour characters’ who follows every stage in striped pyjamas and a cape, who we had seen being interviewed on TV days earlier. He’s taking over from the perennial roadside Satan in his red outfit and trident that rumour has it is heading for retirement. There is already quite a crowd gathering along the road even though we are still hours off the action.

People are stretched out on the village green outside the small bar and community centre with picnics, trays of frankfurters and chips from a pop-up stall, and plenty to drink. Water is more important than beer – the temperature is 30 degrees. In the car park of the bar there is a Tour sculpture – hay bales with bikes perched on top, and ‘Le Noyer’ written out in stones in the hope that the TV helicopters will pick it out. Having the Tour through your village or town is a Big deal.

Sitting on the grass we can see the road, ramps and hairpins, snaking up to the Col high above us between breaks in the trees perched on the mountainside. Two men in a van are nailing a big ‘road narrows’ warning picture to a lamppost. They don’t carry gradient signs, that would just be cruel.

Sitting on the grass we can see the road, ramps and hairpins, snaking up to the Col high above us between breaks in the trees perched on the mountainside. Two men in a van are nailing a big ‘road narrows’ warning picture to a lamppost. They don’t carry gradient signs, that would just be cruel.

In the village we are only a third of the way up the climb. The road is closed to cars, but every minute or so cries of “Allez, allez, allez” reverberate around as people cheer on the steady stream of cyclists making the climb to watch the race from higher up. People stand at the side of the road fist-pumping everyone riding past. It’s a great game for the kids who chase alongside, and there are massive cheers from everyone for the 10 and 11 year olds making the climb with their mum or dad.

There are people here from all over. Whole families are gathered on the grass and along the road. All around us groups are speaking Danish, German, Spanish and Dutch as well as French. We talk to two Norwegian brothers who meet up every year to spend a week at the Tour together.

In the community centre there’s an exhibition, pictures of when the tour has been through Le Noyer before. The photos are of the crowd, the picnics, the characters, the flags, and a few cyclists – but not necessarily those in the race!

Outside the photographer catches my yellow T-shirt ‘Ceci n’est pas le maillot jaune’ (This isn’t the yellow jersey)in his lens, so no doubt I shall be in his show next time.

A burst of car horns announces that a sponsor wagon has arrived. Minutes later everyone is wearing a red-spotted t-shirt – a replica of the ‘King of the Mountains’ jersey worn by the leader in that competition everyday.

Minutes later the Skoda van appears.

It sponsors the Green Jersey for the overall best sprinter. This year three-stage winner Ethiopian Binian Girmay is wearing it, a historic moment: he’s the first black African ever to win even one stage of the Tour. But we are all climbers up here and stick with the red spots. Skoda decides to go with its sunhats instead.

Crowds of people are walking up the road to the top of the Col from the car park. In this heat that is some trek, the gradient above the village averages 8.5%. We are stopping here.

Then the carnival arrives. A convoy of lorries, vans, even a giant Orangina bottle – all interspersed with gendarmes,  national police, sirens, horns, lorry-top DJs and disco hits. There are giant model cyclists, three lorries of giant chickens and then a red cow – who doesn’t love ‘Vache qui ris’ cheese triangles?

national police, sirens, horns, lorry-top DJs and disco hits. There are giant model cyclists, three lorries of giant chickens and then a red cow – who doesn’t love ‘Vache qui ris’ cheese triangles?

Everyone crowds the side of the road trying to catch the promotional goodies tossed out to the crowd. The pros make sure they snare the supermarket shopping bags first to catch or store the booty – key rings, bottle openers, miniature olive oil, packets of sweets, cans of drink, yoghurts.

We wander downhill a little to a bend where we can get a good view. Sure enough, just like Glastonbury, there’s a pole of Welsh flags fluttering in the light breeze. At the Tour it makes sense. The red dragon is there to encourage past Tour winner Geraint Thomas and debutant Welshman Stevie Williams when they get here. There are some other national flags around – but obviously none so stirring.

We’ve been following the race all day on the phone app, watching riders break away; groups split, join up again; attacks, counter-attacks. Actually, we are just watching the Sat Nav dots from the riders’ computers moving on the map, but even that’s exciting. It’s important to understand the tactics and just what is happening when they pass us. By the time they get to us, they will have ridden over 150 km. It’s been gradually uphill all day and then a sharp 1600ft climb over Col Bayard. On our stretch it’s another 2250ft up 12km to the top of Col de Noyer, and if that’s not enough they are still 12.5km from the finish which is mostly uphill too.

With the announcement of ‘Huit minutes’ the atmosphere around us ramps up. Cars shoot up the hill past us, gendarmes, spare bikes, official cars, and loudspeakers. That’s when we hear the helicopters again.

Motorbikes roar up the hill into the bend, two or three splayed across the road. The ones with two front wheels are massive – and loud. The bikes are all black, the riders in leathers, also black. On the second bike, the pillion rider is facing backwards, large video camera in hand. The suddenness, the roar, the exhaust fumes – the sensation is slightly ‘Apocalypse Now’!

Then the breakaway cyclists appear, six of them. They are caning it, the sweat and effort visible. The phone app had said who they were, but its too fast to pick out individuals, even though their speed is reduced by the gradient. A few seconds later, a single rider appears. It’s Englishman Simon Yates, in his bright orange Jayco Alula team kit (all the teams are named after their sponsors). He’s attacked from the following group and hoping to win the stage, guessing that the group up ahead are tiring.

Then there is the large group of riders he’s left behind, about thirty. We look out for Geraint Thomas – our hero – who obliges us by dropping off the group to pick up water from his team car, and passing us really slowly before rejoining.

We look out for Geraint Thomas – our hero – who obliges us by dropping off the group to pick up water from his team car, and passing us really slowly before rejoining.

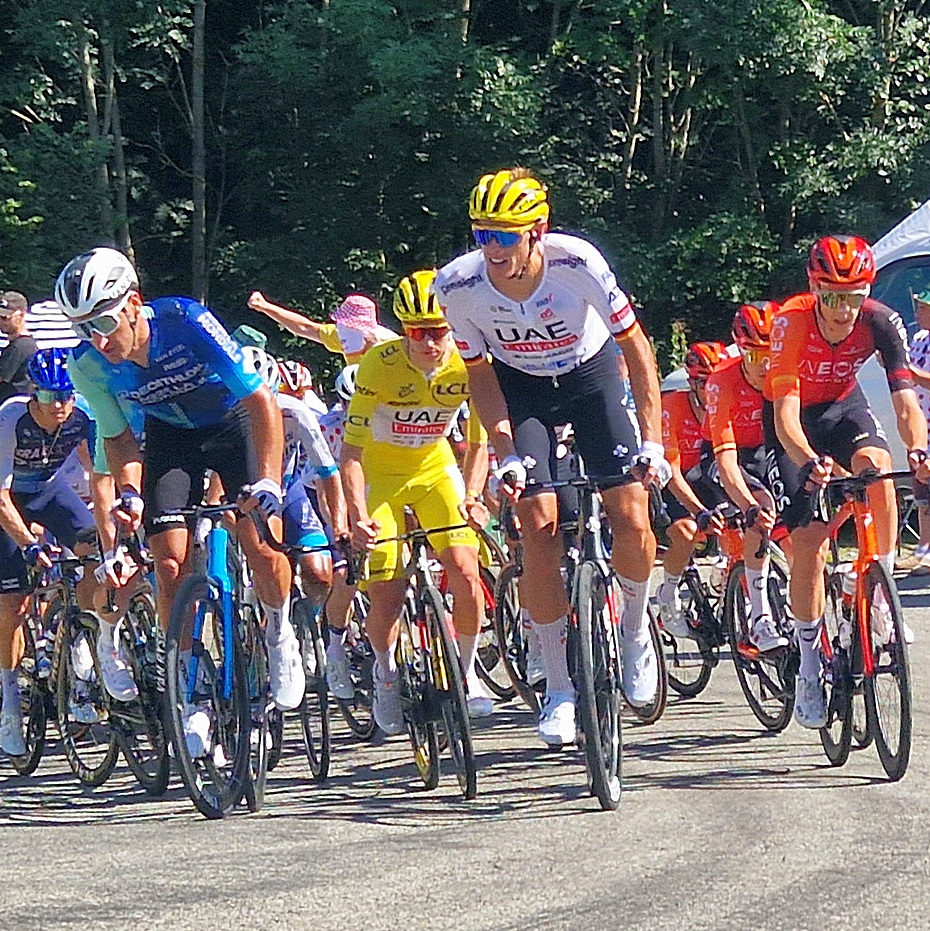

A couple of minutes later the Peleton comes up the hill. These are the riders who are competing for the overall three-week Tour win, not just this stage, and their support riders. Superstar Tadej Pogacar, the current leader in the Maillot Jaune, Vinegaard, and Evenapol all pass – their uphill is way faster than my down!

I spot the village photographer across the road. He is catching the crowd – he’ll probably watch the race on TV later. We take a minute to breathe, and catch up with what we’ve seen.

And then round the bend comes Cav. Surrounded by his team and a couple of other stragglers, he’s struggling with the climb. He has an uncanny skill of getting to the finish just before the cut-off time to stay in the Tour, but climbing is not his thing. He’s a sprinter – he’ll ride every day – 150 to 220km, over any terrain for three weeks, for the chance of winning a thirty second sprint finish. Only a handful of stages offer the chance sprint finish – and he wants to stay in, climbs and all, just for that handful. And he has won 35 times – more stage wins than any other rider in the 110 year history of the Tour. He achieved the record days before, at 39 years old. Legendary. Sir Mark Cavendish.

A few more cars and then the road is empty. We walk back to the car looking high up onto the mountainside, hearing the distant shouting and the helicopters circling above. In the car park we watch the end of the race on a TV sticking out the back of a minivan. We see Carapaz cross the line, he was in the bigger group as it passed us, attacking slightly later. He overtook Yates on the climb as everyone else fell away, a first ever stage winner from Ecuador. He’s almost caught by Pogacar who left the Peleton standing, and flew past everyone except Carapaz on the slope for second place.

We head off down the hill wondering how seeing such a tiny bit of action can be so enthralling, but seriously enthralled. Being there, caught up even for a short while in the biggest, greatest annual sporting event in the world, is unforgettable; the camaraderie of the many thousands of people from across the world all entranced by the event is something to see. The sheer scale of the logistics required to move the whole circus across the country, and set up the race infrastructure every day for three weeks is hard to believe.

But the most amazing thing is the hundred and forty riders who put into climbing that mountain, the second of the day – not just climbing it but racing up in 30 degree heat. It’s exhausting just to think about it, but for them its just one day. They will get up and do it again tomorrow.

Photos: Charlie Hislop

- In Common is not for profit. We rely on donations from readers to keep the site running. Could you help to support us for as little as 25p a week? Please help us to carry on offering independent grass roots media. Visit: https://www.patreon.com/incommonsoton