By Martin Brisland. Image with permission from Southampton City Council Cultural Services.

The Titanic story is one that continues to fascinate 111 years after the event. Out of the 908 crew onboard, there were around 688 crew deaths. Sadly, 550 people with a Southampton address perished in the sinking on the night of 14/15 April 1912.

The impact was devastating, especially on the close knit communities of Chapel and Northam. The National Coal Strike of 1912, which only ended on the 6th April, meant a large number of local men had been unable to work on the ships since February and many families were on the brink of destitution.

One Southampton woman lost eight relatives, her husband, a son, two brothers and four cousins. In one school alone in the Northam area of Southampton, one hundred and twenty-five children lost their fathers. In an edition of the local newspaper, Southampton & District Pictorial (Wednesday 24th April 1912), a photograph was printed of these unfortunate youngsters. It carried the title ‘Toll of the Titanic’ and underneath the caption, the following was printed:

“Everyone of the children pictured above has lost a relative or relatives by the foundering of the vessel, and they all attend Northam School. Several of them are left orphans, others have lost fathers, brothers, uncles and cousins. There are something like 140 all told in this one school who will never forget the great ocean tragedy.”

The Mayor of Southampton, Henry Bowyer, set-up a room where money from the Southampton Titanic Relief Fund was distributed to the most needy. It was decided that they needed a ‘Lady Visitor’ to help bereaved families. Such a job would be done today by a social worker but 1912 was pre Welfare State. The committee’s preferred choice was for a woman who was not resident in Southampton, presumably because she would bring more objectivity to the task. However, the eventual appointment was Miss Ethel Maude Newman, 36, who lived all her life at Hawthorn Cottage on the Common. The site later became the home to Southampton Zoo and is now occupied by the Hawthorns Urban Wildlife Centre. Miss Newman was listed on the 1911 census as secretary to a local charitable organisation.

Miss Newman earned an annual salary of £100 plus travelling expenses. She would ride her bike around Southampton visiting families who were in receipt of monies from the Southampton Fund, checking on their ongoing welfare. John Bartlett May later recalled that “she used to ride her upright bicycle with her dalmatian dog always running beside her and she used to come regularly, once or twice a month”.

The distribution of the Relief Fund was very much along Victorian class and gender lines. The widows were not considered competent to manage their own budgets and so money was doled out in small, frequent amounts which compounded the poverty in which they lived. The social attitude of the day was very much to group people as the ‘deserving’ and the ‘undeserving’ poor. Relief fund recipients had to be seen to be ‘deserving’ poor and any hint of moral looseness or drunkenness meant that income would cease immediately.

Miss Newman seems to have managed to balance the fine line between befriending her charges while simultaneously ensuring that domestic situations were satisfactory. She was not universally popular and on one occasion her bicycle ended up in the River Itchen. Often she was able to help families in very practical ways, including setting up apprenticeships like one to French and Sons Bootmakers – a firm established in 1803 and still going strong in Bedford Place today.

Miss Newman continued to work for the fund until her death in 1940. She is buried in the recently restored family grave in Southampton Old Cemetery.

For more information see The Titanic and the City of Widows it Left Behind book. It is written by local author Julie Cook who lost her own great grandfather, leaving his wife Emily to bring up five children.

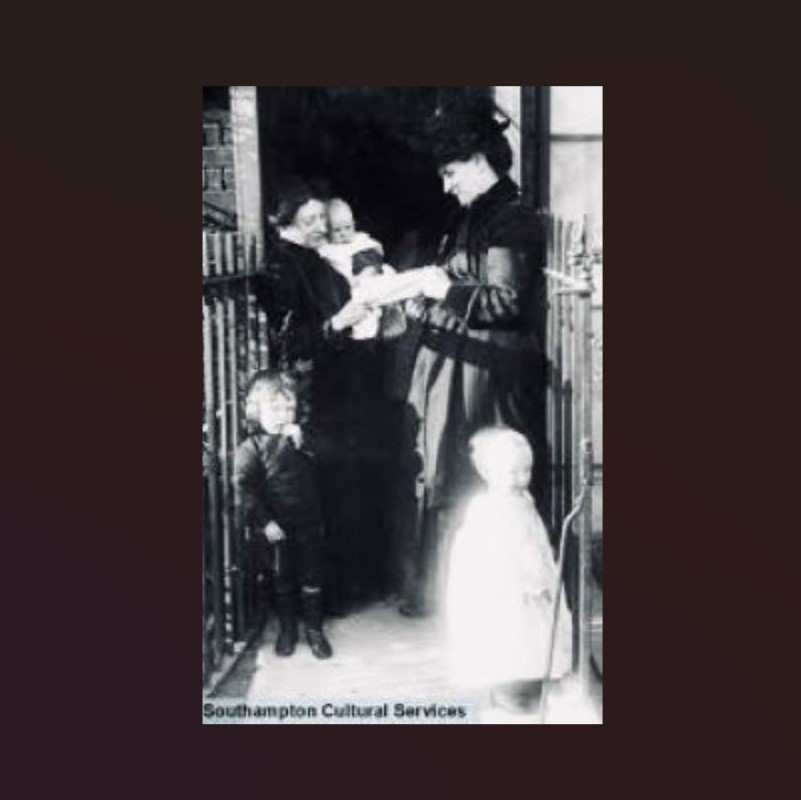

- The main image is thought to be a staged newspaper photo of Mrs Hurst receiving the bad news that her husband was amongst those lost at sea.

- In Common is not for profit. We rely on donations from readers to keep the site running. Could you help to support us for as little as 25p a week? Please help us to carry on offering independent grass roots media. Visit: https://www.patreon.com/incommonsoton

You may also like:

Heritage: Southampton street names’ connections to Britain’s ignoble colonial past

Heritage: remembering Southampton historian Elsie Mary Sandell

Heritage: Eleanor Coade, the remarkable Georgian businesswoman