by Owen Hatherley.

This essay was originally written as a lecture to accompany Southampton photographer Rachel Adams’ exhibition Life Is Brutalist: a portrait of Wyndham Court, celebrating the 50th anniversary of the city’s landmark building. Due to the coronavirus pandemic, the planned physical exhibition had to be called off, but Rachel’s striking photographs can be viewed in the online exhibition, featuring interviews with Wyndham Court residents and a soundscape from Southampton band Band of Skulls: https://www.lifeisbrutalist.com/

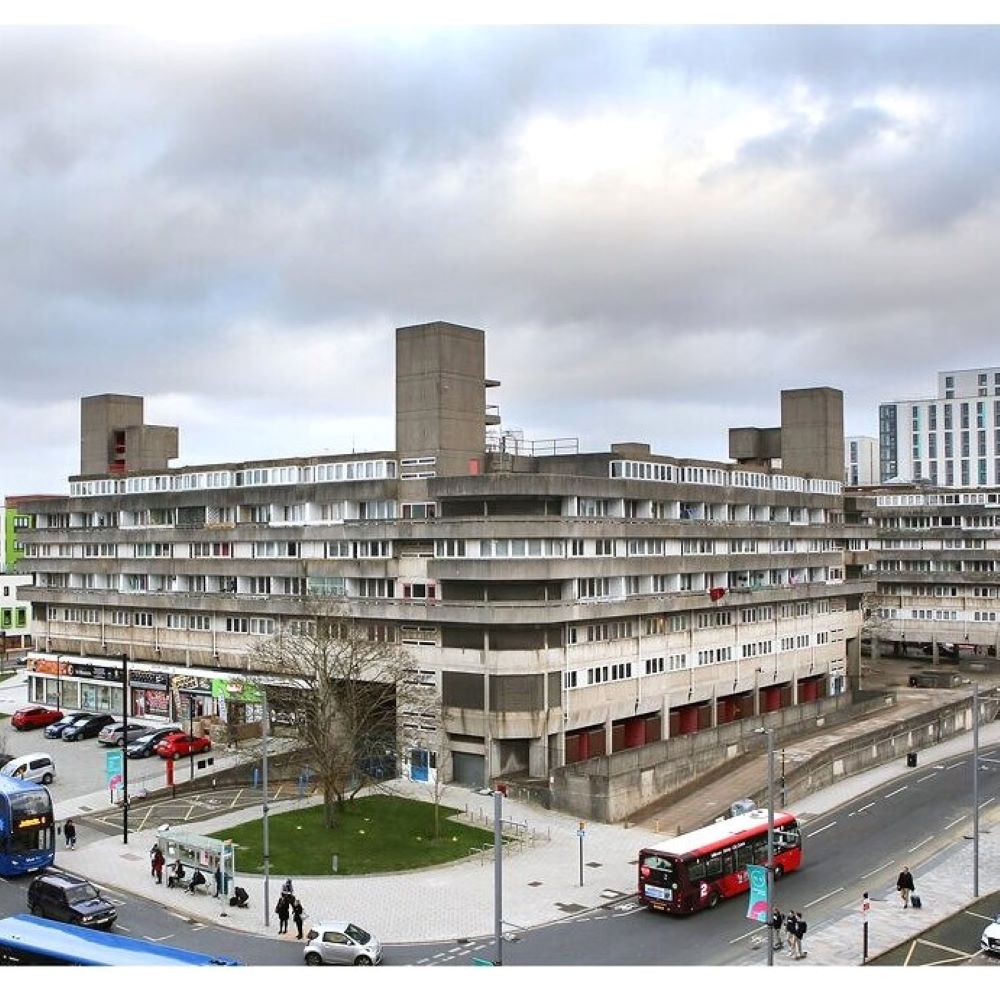

If you’re from Southampton, it can sometimes feel as if your hometown doesn’t really properly exist. For a city of a quarter of a million people whose history stretches back for over a thousand years, there seem to be no books written about it – aside from ‘How It Looked In The Olden Days’ picture books – no novels, no TV shows, no films. It sprawls across South Hampshire, and though it is stopped briefly by the M27 and the Green Belt, its suburbs and exurbs keep on going until it eventually becomes, almost imperceptibly, somewhere else – Winchester, Portsmouth. It seldom feels like it’s really a city – only in its football fandom, and sometimes, in its trade union and socialist politics, and in its anti-racist activism (the stand of the multicultural community in Derby Road against the Immigration Street documentary being a rare example that was noticed outside the city) does it ever coalesce as a civic community of any kind. And yet, there’s this building at the centre of it, that as soon as you’re out of the railway station, says YOU ARE HERE. That’s one of the reasons why I, and many other people, think of Wyndham Court, that improbable Brutalist ocean liner of council housing, standing on its concrete stilts overlooking the docks and the city centre, to be the most important building in the city. If you state this opinion in some company, people will look at you askance. Isn’t it an Eyesore? Doesn’t it look like it’s in the Eastern Bloc? Can’t we paint it in bright colours? Why is it so dirty? So if you come to praise it, you need to do quite a bit of justifying yourself.

The Civic Regiment

The usual explanation of why Southampton seems to lack a certain identity or civic pride – certainly the most popular one among Sotonians – is that the town centre was obliterated in the course of a few days in 1940, and nothing of real value was constructed to take its place. Alternatively, one could argue – my preferred argument – that it’s a consequence of the city’s dismantlement of its previously strong culture of planning and civic architecture from the 1970s onwards, and the encouragement of sprawl and cheap, retail-driven development. But really these issues have a longer history than either the 1940s or the 1980s. In a recent essay on Southampton Civic Centre, the architectural historian Neal Shashore locates this vagueness in what is, along with Wyndham Court, the most immediately striking and large-scale 20th century building in the city – the sprawling civic complex planned in the late 1920s and built across the 1930s.

Southampton Civic Centre, he writes, ‘is perhaps the archetypal set of grouped public and municipal buildings in England in the interwar period, not only in their design and construction, but in the manner of their procurement and pre-construction’. Architecturally in an extremely mild form of classicism, executed in Portland stone, it was actually a response to the fact that Southampton – unlike, it pains me to say, neighbouring Portsmouth – never had an architecturally impressive 19th century Town Hall, or public buildings of any real note; not only was the Civic Centre relatively pioneering for the time in grouping together functions that were spread out in other cities, in some of these cases it was the first time the city had the building in question at all – so while pre-existing council offices, courts and police moved into the new building, it was also the city’s first proper concert hall, art gallery and central library. As Shashore points out, it was ‘also a focus of political battles, typical of the time, between the Labour Party keen to secure working-class housing, and an anti-socialist coalition of Liberals and Conservatives’. The importance of this political contestation can’t be gainsaid in Southampton’s case. Unusually for the south, it has never been a heartland for the Conservative Party, but unlike in similar cities in the north, Labour have seldom had large majorities here either. Between the 1920s and 1980s, the council mostly fluctuated between Labour and the Tories, and it has only really been reliably Labour in the last 30 years – and even then, the Conservatives took control for one term at the turn of the 2010s.

The combination of civic virtue and conservatism in the building comes out in the approach of its architect, E. Berry Webber, to the notion of ‘civic pride’. Shashore cites a speech of his where he declared ‘the provision of our public buildings is something more than a mere job – its moral effect can be great and it deserves the finest efforts of us all. Civic pride deserves no sneer. Civic pride means good citizens, just as pride in a regiment produces good soldiers’. Yet what precisely about Southampton itself was the building declaring itself proud of? In his analysis of the ‘vague’ maritime motifs in the Civic Centre’s rich interiors, Shashore finds nothing specific to the city – ships built in Portsmouth, motifs taken from Venice, when Genoa was the city Southampton once traded with, and lots of imagery of waves and distant colonial outposts. ‘The new centre of centres for civic life in Southampton’, he writes, ‘is thus decorated with motifs and emblems about being anywhere else but Southampton’. He argues on the basis of this, and J.B Priestley’s inability to find the city centre when visiting the town for his Depression-era English Journey, that ‘the origins of Southampton’s lack of civic sensibility, of a place unfulfilled and ill-defined, were older than the shock and destruction caused by the Blitzkrieg in the Second World War…interesting and richly ornamented as Southampton Civic Centre was, it failed in the eyes of contemporaries to register a genius loci’.

The combination of civic virtue and conservatism in the building comes out in the approach of its architect, E. Berry Webber, to the notion of ‘civic pride’. Shashore cites a speech of his where he declared ‘the provision of our public buildings is something more than a mere job – its moral effect can be great and it deserves the finest efforts of us all. Civic pride deserves no sneer. Civic pride means good citizens, just as pride in a regiment produces good soldiers’. Yet what precisely about Southampton itself was the building declaring itself proud of? In his analysis of the ‘vague’ maritime motifs in the Civic Centre’s rich interiors, Shashore finds nothing specific to the city – ships built in Portsmouth, motifs taken from Venice, when Genoa was the city Southampton once traded with, and lots of imagery of waves and distant colonial outposts. ‘The new centre of centres for civic life in Southampton’, he writes, ‘is thus decorated with motifs and emblems about being anywhere else but Southampton’. He argues on the basis of this, and J.B Priestley’s inability to find the city centre when visiting the town for his Depression-era English Journey, that ‘the origins of Southampton’s lack of civic sensibility, of a place unfulfilled and ill-defined, were older than the shock and destruction caused by the Blitzkrieg in the Second World War…interesting and richly ornamented as Southampton Civic Centre was, it failed in the eyes of contemporaries to register a genius loci’.

But at the same time as it was a pioneer at the Civic Centre, Southampton was also one of the major cities to develop non-market housing in any large scale in the inter-war years, far more so than any other city in the south outside of London and Bristol. The best known examples of this were only semi-public – the co-operative ‘garden city’ schemes designed by the Quaker architect Herbert Collins in the leafy northern suburbs such as Highfield and Swaythling. These are models of relaxed, elegant and green housing, the state of the art for their time – but like much garden city housing, it has long been a preserve of the affluent. In response to this, and the 1924 Housing Act passed in the brief Labour government of that year, Southampton County Borough (as it then was) started building large estates such as the Flower Estate in Swaythling (which features repeatedly in the paintings of the artist Eric Meadus) and Merry Oak in Bitterne. The sociologist John Astley, who grew up in Merry Oak, describes it as having been ‘planned holistically, with the spaces between the roads and the buildings contributing to the overall feeling of inclusion…there is a desire to create aesthetic interest, adventure; excite the eye, and take it on a journey’.

Merry Oak was visited by the Labour Housing Minister Arthur Greenwood in 1930, as a ‘blueprint’ estate, and was celebrated in the 1931 book HOUSING – Housing Schemes Carried out by the County Borough of Southampton. This pointed out that ‘a large proportion of Southampton’s working-class population are dock labourers, whose wages do not allow of large expenditure in house rents’, for which reason most houses built didn’t have ‘parlours’, considered essential for respectability at the time. But unlike in other industrial port cities such as London, Hull or Liverpool, there was very little inner city council housing, though scattered tenements survive near the later Holyrood estate. Aside from the Civic Centre, itself sprawling and vague. All the attention in Southampton was going into the suburbs, which were being reshaped into miniature garden cities for the deserving poor. And then, the centre wasn’t there any more.

Merry Oak was visited by the Labour Housing Minister Arthur Greenwood in 1930, as a ‘blueprint’ estate, and was celebrated in the 1931 book HOUSING – Housing Schemes Carried out by the County Borough of Southampton. This pointed out that ‘a large proportion of Southampton’s working-class population are dock labourers, whose wages do not allow of large expenditure in house rents’, for which reason most houses built didn’t have ‘parlours’, considered essential for respectability at the time. But unlike in other industrial port cities such as London, Hull or Liverpool, there was very little inner city council housing, though scattered tenements survive near the later Holyrood estate. Aside from the Civic Centre, itself sprawling and vague. All the attention in Southampton was going into the suburbs, which were being reshaped into miniature garden cities for the deserving poor. And then, the centre wasn’t there any more.

Shellshock in Southampton

In an era where the – actually unused in wartime – Keep Calm and Carry On poster is considered to sum up how Britain experienced the Blitz, it is striking to read accounts from the time about just how much anger and panic there actually was in Southampton as a consequence of its carpet-bombing by the Luftwaffe. There was almost open revolt, caused by the sudden absence of the city’s government, who absconded from that new Civic Centre. In 1940, rather than happily bunkering down and carrying on, refugees spread out in an arc across the surrounding countryside, to Eastleigh, Chandlers Ford, Otterborne, Twyford, Shawford, Winchester, Romsey, New Forest, leaving a small and badly sheltered working-class population, who didn’t have rural relatives to stay with, to bear the brunt. The city council’s leaders were among those that departed, which actually led, extraordinarily, to a brief RAF coup in the city, where for a time it was run as a military dictatorship, with the hapless civilian leadership in hiding. ‘The airmen deeply criticised the breakdown’, writes Tom Harrisson in his Living Through the Blitz. ‘They were scathing about the leadership of the city as a whole’, who had ‘quit intellectually, some of them actually, physically’.

Mass Observation, the left-leaning research group that Harrison chaired, compiled a report in 1940 about the reactions to the bombing of Southampton. They found that ‘over and over again … homeless, old, pregnant, ill and anxious-to-evacuate people … did not know where to get the relevant forms or information. The comment of one woman is not typical, but not too far away from it. “Everywhere you go they tell you you can’t go there.”’ On George VI’s visit to the city, intended as a way of cheering up the battered populace, ‘the party passed unnoticed. When a large public later learned of their visitors, initially from the radio, the response was far from uniformly enthusiastic … “I suppose they do a certain amount of good coming around but I wish they’d give me a new house” [was] among the more friendly comments’. Or, as another put it more bluntly, ‘everybody knew [the council] got out of Southampton every night and only came back to meet the King and Queen’.

It’s this experience that explains some of the radicalism of the Plan for Southampton, compiled in the aftermath of the Blitz and published in 1942 by the planners Adshead. Imagining even more suburban council estates – it suggested building one on the Test estuary in Millbrook – it also had some dramatic ideas for the city centre, where the bombed out main shopping street, Above Bar, would be replaced by a grand circus, inspired by Bath, and a two-level precinct, inspired by the Rows in Chester. Looked at in Adshead’s drawings, these are still classical, like the Civic Centre, but the planning ideas were much bolder – a new spaciousness, and interest in multiple levels and views, had come into Southampton architecture. It was also rejected by the time the city came to reconstruct. After the war, Southampton Labour Party fought, and won overwhelmingly, a local election on the basis of nationalising land in the city centre in order to execute the plan – but both large and small businesses and landlords were disgruntled, and public meetings called by the Labour Council to publicise the plan were sparsely attended. As the historian Junichi Hasegawa points out, ‘the financial difficulties caused by the Blitz, insufficient government financial and other assistance for reconstruction, and pessimistic prospects for the city’s industrial future, all forced bold planning ideas to yield to economy and expediency.’

It’s this experience that explains some of the radicalism of the Plan for Southampton, compiled in the aftermath of the Blitz and published in 1942 by the planners Adshead. Imagining even more suburban council estates – it suggested building one on the Test estuary in Millbrook – it also had some dramatic ideas for the city centre, where the bombed out main shopping street, Above Bar, would be replaced by a grand circus, inspired by Bath, and a two-level precinct, inspired by the Rows in Chester. Looked at in Adshead’s drawings, these are still classical, like the Civic Centre, but the planning ideas were much bolder – a new spaciousness, and interest in multiple levels and views, had come into Southampton architecture. It was also rejected by the time the city came to reconstruct. After the war, Southampton Labour Party fought, and won overwhelmingly, a local election on the basis of nationalising land in the city centre in order to execute the plan – but both large and small businesses and landlords were disgruntled, and public meetings called by the Labour Council to publicise the plan were sparsely attended. As the historian Junichi Hasegawa points out, ‘the financial difficulties caused by the Blitz, insufficient government financial and other assistance for reconstruction, and pessimistic prospects for the city’s industrial future, all forced bold planning ideas to yield to economy and expediency.’

Only one major part of the 1942 Plan was built – the Kingsland Estate, around the formal public space of Cossack Green. Built in 1949 to the designs of Johnson and Crabtree (the latter the architect of the Peter Jones department store in Chelsea), it is the first landmark in Southampton’s extensive adventure in modernist planning. Next to, and sheltered by trees from, the main railway line into London, it consists of several curved low-rise blocks, with big balconies, rendered white and pale green. Behind this at Cossack Green itself are concrete terraces around two nude sculptures of Adam and Eve. It’s still a little model of democratic, attractive social architecture. Above Bar, though, was much less impressive. In 1967, David Lloyd and Nikolaus Pevsner wrote in the local volume of The Buildings of England – Hampshire and the Isle of Wight that it ‘has the look that a main street of an up-and-coming Middle West town might have had in the early 1930s if there had been planning control and Portland stone… rebuilding took place mostly c1950-5 – alas, in a thoroughly commonplace manner, in watered-down neo-Georgian or half-hearted modernistic styles, or in compromises of both. There are only two buildings worth looking at in the whole of Above Bar’. The only immediately post-war building they recommend visiting is the since-demolished streamline moderne Ocean Terminal (oddly, they missed the Kingsland Estate entirely), which was the first large-scale public building in Southampton to take its cue in scale and design from the enormous ships that then, as now, constantly came in and out of Southampton Water. Elsewhere, however, it seemed the city had settled for vagueness and timidity.

Only one major part of the 1942 Plan was built – the Kingsland Estate, around the formal public space of Cossack Green. Built in 1949 to the designs of Johnson and Crabtree (the latter the architect of the Peter Jones department store in Chelsea), it is the first landmark in Southampton’s extensive adventure in modernist planning. Next to, and sheltered by trees from, the main railway line into London, it consists of several curved low-rise blocks, with big balconies, rendered white and pale green. Behind this at Cossack Green itself are concrete terraces around two nude sculptures of Adam and Eve. It’s still a little model of democratic, attractive social architecture. Above Bar, though, was much less impressive. In 1967, David Lloyd and Nikolaus Pevsner wrote in the local volume of The Buildings of England – Hampshire and the Isle of Wight that it ‘has the look that a main street of an up-and-coming Middle West town might have had in the early 1930s if there had been planning control and Portland stone… rebuilding took place mostly c1950-5 – alas, in a thoroughly commonplace manner, in watered-down neo-Georgian or half-hearted modernistic styles, or in compromises of both. There are only two buildings worth looking at in the whole of Above Bar’. The only immediately post-war building they recommend visiting is the since-demolished streamline moderne Ocean Terminal (oddly, they missed the Kingsland Estate entirely), which was the first large-scale public building in Southampton to take its cue in scale and design from the enormous ships that then, as now, constantly came in and out of Southampton Water. Elsewhere, however, it seemed the city had settled for vagueness and timidity.

The Golden Age of Concrete

In 1948, the Liverpool-educated modernist architect Leon Berger was appointed the Borough Architect. From then, he ‘instituted a programme for a thousand homes every year’, according to the architectural historian Elain Harwood – one of the largest programmes in the country, facing the problems created both by the wartime destruction and the extensive slums around the medieval walls. Harwood roots this in the interwar years – ‘Southampton’s housing programme most closely approached Sheffield’s in its range and vitality, thanks to its choice of private architects and a tradition of decent housing’ that began in the 1920s with Cunard’s company housing and the garden city schemes of Herbert Collins – but the difference can partly be seen in how much more modern and urban the new buildings were.

In 1967, David Lloyd and Nikolaus Pevsner registered the enormous change in the city between the aftermath of the war and the sixties. ‘For several years after the war’, they wrote, ‘the town seemed stunned and half-ruined, but since the early fifties it has made a remarkable recovery. It is now bigger in population and bigger in status than it was before the war; it is well on the way to establishing itself as the regional capital of an important part of England’. One of the most important aspects of this was the fact that ‘since about 1955, the city has undergone an architectural revolution.’ This was led by the architects in the Civic Centre – ‘the City Architect’s Department under L. Berger has produced varied and often distinguished work’, of which ‘the most impressive’ were the new Northam Estate and the (demolished) Swimming Baths. At the University, ‘(Basil) Spence’s more recent buildings make an extraordinary contrast in scale and inventiveness’ with their neo-Georgian predecessors.

In 1967, David Lloyd and Nikolaus Pevsner registered the enormous change in the city between the aftermath of the war and the sixties. ‘For several years after the war’, they wrote, ‘the town seemed stunned and half-ruined, but since the early fifties it has made a remarkable recovery. It is now bigger in population and bigger in status than it was before the war; it is well on the way to establishing itself as the regional capital of an important part of England’. One of the most important aspects of this was the fact that ‘since about 1955, the city has undergone an architectural revolution.’ This was led by the architects in the Civic Centre – ‘the City Architect’s Department under L. Berger has produced varied and often distinguished work’, of which ‘the most impressive’ were the new Northam Estate and the (demolished) Swimming Baths. At the University, ‘(Basil) Spence’s more recent buildings make an extraordinary contrast in scale and inventiveness’ with their neo-Georgian predecessors.

Reading the 1964 Survey of Southampton and its Region, you get a sense of a city whose civic fathers were pretty pleased with their record. ‘A community like Southampton knows fairly well to whom it is indebted for the day-to-day conduct of the town’s services and affairs….so the council’s chief officers and their staffs, and in particular those who administer the family services responsible for health, welfare and the care of children, occupy a unique place in the community’; they are quick too to point out that ‘with these it is right to include the trade union officers.’ They contrast this with the laissez-faire politics and economics of the 19th century, where all was left to the market – ‘the contemporary municipality is in many ways returning to an overall concern for the economic, social and personal welfare of the community such as it enjoyed before the restrictive attitude to the powers of local authorities developed in the nineteenth century.’ In fact, the balance of public and private had shifted very radically – ‘for private housing needs there will soon be little land available other than that in possession of the local authority’.

This was not all about high-rises and soaring council flats; along with this, the City Architects were responsible for the restoration of God’s House Tower and the Wool House, the conversion of historic buildings into museums, the creation of public access paths and walkways along the Walls, and the layout of new public spaces such as Mayflower Park and Riverside Park. The planning ideas behind this aimed to stress the city’s sprawling, green expanse as a virtue rather than a source of a lack of identity. The city’s Development Plan, which was approved by government in 1956, concentrated on dense, urban housing and large public green spaces. ‘Today the pressure of high land values and actual land shortage, together with trends in modern housing development, are increasing building density and are studding the townscape with tall blocks. Pride in the central parks and deep concern for the preservation of open spaces have been turned by the planning authority into a policy of open space development covering all parts of the town. This is an attempt to get the best of two worlds, of “openness” and high population density’. In his own contribution to the Survey on architecture as an ‘aspect of the civic scene’, Berger writes’ of how the department were then planning ‘great areas on the periphery of the town. The latest of these, Lordshill (is) virtually a town of itself’ Modestly, he writes of how ‘the clearance of slums has already produced some notable schemes. Messrs. Lyons and Israel’s Holyrood flats are sensitively handled’, and there is ‘a highly individual essay in the design of tall blocks of flats’ at Eric Lyons’ Castle House, while ‘a decrepit area at Northam has been transformed by mixed development of maisonettes and another tall block of flats, the Council’s first’. Unmentioned, even more modestly, is the most successful of all Berger’s projects – the angular and elegant Brutalist concrete ‘Southampton Bench’, designed in-house in the Civic Centre and then copied all over the country and beyond.

While they write of the city’s architecture in 1967, Pevsner and Lloyd have some anxiety about the increasingly giant scale of the council’s housing. Shirley Towers, Albion Towers and Sturminster House, the council’s only experiments with large panel concrete system-building, were all enormous, both tall and wide, and had beneath them maisonettes of two-to-four storeys, a contrast they found discordant and melodramatic. At Thornhill, they note, worriedly, ‘the towers undoubtedly have a majestic urban character. But is it visually or socially right to place buildings of such hugely urban scale, with such a concentration of population, far on the suburban fringe?’ Though, they do look forward to the similar towers being built as ‘effective landmarks from the water’ at a similarly suburban site on Southampton Water at Weston Shore. Wyndham Court came just after the book was published – planned in 1966, it was only completed in 1969 – and brought both a peak and an end to the project of municipal modernism in Southampton.

While they write of the city’s architecture in 1967, Pevsner and Lloyd have some anxiety about the increasingly giant scale of the council’s housing. Shirley Towers, Albion Towers and Sturminster House, the council’s only experiments with large panel concrete system-building, were all enormous, both tall and wide, and had beneath them maisonettes of two-to-four storeys, a contrast they found discordant and melodramatic. At Thornhill, they note, worriedly, ‘the towers undoubtedly have a majestic urban character. But is it visually or socially right to place buildings of such hugely urban scale, with such a concentration of population, far on the suburban fringe?’ Though, they do look forward to the similar towers being built as ‘effective landmarks from the water’ at a similarly suburban site on Southampton Water at Weston Shore. Wyndham Court came just after the book was published – planned in 1966, it was only completed in 1969 – and brought both a peak and an end to the project of municipal modernism in Southampton.

First of all, it was designed for a different type of council tenant, rather than the dockers and industrial workers for whom Millbrook, Lordshill, Thornhill, Holyrood and others were built. As Elain Harwood describes it, it had what were described as ”economic’ rents’. That is, they were higher than most of the city’s council housing, ‘targeted at professionals’. That the council would also built housing for the city’s middle class as well as the working class is an idea that seems extremely radical after the Right to Buy cut a swathe through the rented stock of so many councils from the early 1980s onwards, turning it into a stigmatised form of housing – though looked at more critically, it also seemed to suggest, unlike the earlier, very high quality Castle House, that the city centre middle class housing should be of a superior quality to the ordinary stuff for factory workers out in Millbrook. I was once told by a reliable source that the council had a policy of housing its architects in the buildings they designed, a useful measure of ensuring that they would design something that they themselves would be happy to live in – but that the architects drew the line at living in Millbrook.

As a planning idea, Wyndham Court was urban. All Southampton’s ideas for expanding greenery and taking the Victorian parks and the tree-filled route from the Common through to the Avenue as the city’s planning principle have gone out of the window. This was big city architecture, stark and hard. 184 flats, shops, underground parking, and a system of raised walkways to, apparently, ‘satisfy the council’s wish that pedestrians should be able to use the site as a short-cut to the station from the new suburbs in the north and west’. This also necessitated the ‘pilotis’, the tall concrete columns that raise the flats high above the ground, deliberately there to let people walk through (hence providing ‘eyes on the street’, as Jane Jacobs put it – and maybe this constant activity is one reason this has never been considered a ‘problem estate’), but treated with flamboyance in the design. Architecturally, there are two things that really mark out Wyndham Court. It is a full-scale, raw concrete Brutalist building, while most of the city’s housing under Berger was in a milder, mainstream modernist vein with plenty of yellow and purple brick. The choice of a white concrete with Portland stone in its aggregate was, as Harwood points out, intended to be ‘complimentary’ with the Civic Centre (dirt has since made this invisible), and the scale of the building was kept relatively low so as not to crowd out its Clock Tower. And in terms of the building’s references, a clue could be found in a note by Pevsner and Lloyd on the same architects’ Wimpson School, of 1953. It had ‘three funnel-shaped features on the skyline containing the service equipment, causing the school to be nicknamed ‘the Queen Mary’.’

The designers of Wyndham Court, the London firm of Lyons, Israel and Ellis – also the designers of some low-rise housing in the Old Town, several schools, and the Holyrood estate – were not stars, but many who worked for them would go on to be. Famous modern architects like James Gowan, James Stirling – after whom the Stirling Prize for the best British building was named – Alison and Peter Smithson, Richard MacCormac, John Miller and Alan Colquhoun, all passed through its offices. After the firm closed, one of its architects, Neave Brown – who would later become famous for a series of heroic schemes for Camden Council such as Alexandra Road and Fleet Road – wrote an essay on the firm for a commemorative book. ‘Although it attracted a galaxy of talent to work at the drawing board, the office never raised its voice in debate, thrust itself to the fore or aspired to glamour. It was there to get on with the job…the achievement of Lyons Israel Ellis is that they raised the work of that middle level to a quality equal (and at times superior) to that of the stars’. This all seems a fitting ethos for a city which has never made a big fuss of itself.

Wyndham Court has cousins in other buildings by the same firm elsewhere – the plan around a central square was tried out in the National Sea Training School in Gravesend, and its aggressive and angular style from the massive Westminster Polytechnic, in Marylebone. Neave Brown describes this as having been ‘designed in a Constructivist tradition…affirmative and pervaded by an optimism (and) a drama…that denies front and back, facade, inequality of inner and outer space. It declares a faith that the actual and necessary elements themselves are enough – stairs, vents, chimneys, pulleys – and that the paraphernalia of a machine building beautifully assembled can acquire symbolic and poetic value’. All of this applies doubly to Wyndham Court. Here, Brown, who knew what he was talking about having participated in the office, describes how the idea emerged from an ordinary commission into something much more important.

‘At Southampton, what started as a typical analysis of housing and other functions into discrete units, which might have led to a mixed development, became fused by a violent reappraisal to become one continuous urban figure, a coil and a block, with inner and outer perimeters. The fabric of the area was already destroyed, without an urban structure to maintain. The block does not reassert frontage, but does achieve a powerful and unifying, citadel-like identity. Its remarkable plasticity is achieved by organisation, by grouping and layering of dwellings, by the use of access and secondary elements, and by a direct expression without distortion. It deserves a place in the history of high-density housing, rejecting mixed development for urban propositions’.

‘At Southampton, what started as a typical analysis of housing and other functions into discrete units, which might have led to a mixed development, became fused by a violent reappraisal to become one continuous urban figure, a coil and a block, with inner and outer perimeters. The fabric of the area was already destroyed, without an urban structure to maintain. The block does not reassert frontage, but does achieve a powerful and unifying, citadel-like identity. Its remarkable plasticity is achieved by organisation, by grouping and layering of dwellings, by the use of access and secondary elements, and by a direct expression without distortion. It deserves a place in the history of high-density housing, rejecting mixed development for urban propositions’.

Today, it seems the building is finally receiving that place in the history of Britain’s twentieth-century housing. It was listed by English Heritage (now Historic England) in 1998 – even the instalment of UPVC windows, which has stopped many listings, was not enough – and has appeared in numerous photo-books, Tumblr posts and Instagram accounts in the last decade. It is Southampton’s equivalent of London’s Barbican, South Bank or Brunswick Centre, Sheffield’s Park Hill, Preston’s Bus Station, and Birmingham’s (demolished) Central Library, and it is every bit as good as these. It is surely only a matter of time before it joins these on T-shirts, tea towels, mugs and coasters, as Brutalism becomes the new Victoriana for 20-and-30-something hipsters.

But in the story of Southampton, it means something different. We can celebrate it now as an image of civic pride, in which it is part of a history stretching back into the early 20th century, and an emblem of the city’s forgotten post-war experiment in socialist planning, but it is also, really, the end of something. It was the last major building of its architects’ career, and it was also both the last really dramatic modern building, and the the last council housing scheme of any real size, in the city of Southampton. In the 1980s, the pleasant little Postmodernist red brick houses of the Mandela Way estate, actually visible from the balconies of Wyndham Court, were the last gasp of council housing here, and they do everything to turn their back on the city architecturally – the exact opposite of the open, proud and loud architecture of the 1969 building. Since then, all the trends noticed long before Wyndham Court was built have returned. Buildings are vague, cheap, and dull, housing is overwhelmingly private, local character in its architecture is non-existent; even the green space so prized by 1920s and 1930s planners has disappeared from new development. Business rules and local government follows, just as in the 19th century. Recently a ‘cultural quarter’ – nice to have, to be sure – was built the other side of the Civic Centre, and it consisted of some shop fronts between luxury flats and a Nando’s.

There is a generation of people in Southampton for whom this isn’t good enough – they want to live in a city, not in a giant megamall convenient for the M27 and the M3. One day, the city’s politics will change, radically. When it does, this building and the ideas behind it will finally get the respect they deserve. And then on that glorious day, Wyndham Court might even get cleaned.

Owen Hatherley is the author of several books, including The Ministry of Nostalgia, The Adventures of Owen Hatherley in the Post-Soviet Space and the forthcoming Red Metropolis: Socialism and the Government of London, and is culture editor of Tribune.

Further Reading

John Astley, Access to Eden – The Rise and Fall of Public Sector Housing Ideals in Britain (2010)

David Gray and Alan Forsyth, Lyons Israel Ellis Gray – Buildings and Projects, 1932-83 (1988)

Tom Harrison, Living through the Blitz (1990)

Elain Harwood, Space, Hope and Brutalism – English Architecture, 1945-1975 (2015)

Elain Harwood, England’s Post-War Listed Buildings (2015)

Junichi Hasegawa, Replanning the Blitzed City Centre (1992)

FJ Monkhouse, A Survey of Southampton and its Region (1964)

Nikolaus Pevsner and David Lloyd – The Buildings of England: Hampshire and the Isle of Wight (1967)

N.E Shashore, ‘Southampton Civic Centre – Patronage and Place in the interwar architecture of public service’, in Twentieth Century Architecture 13: The Architecture of Public Service (2018)