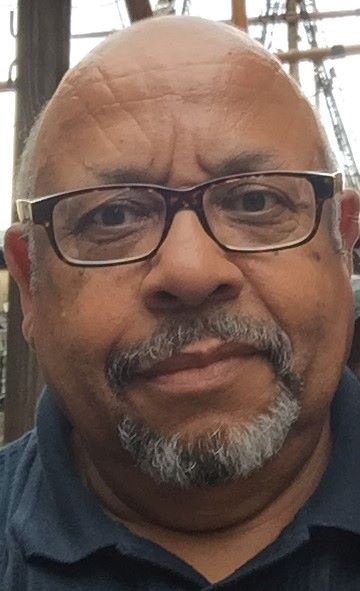

by Jim Baker.

For many Black people, Southampton is a place of arrival but for Wales it is a place of forced repatriation after both World Wars; Black merchant seaman who served Britain and were then forced to leave by government and trade unions. As was Hull (World War 2) for 4,000 Caribbean RAF Airman (1) and Black soldiers (2) and Port Horizon Project (3).

I hope this article makes sense. Sometimes you can be too close to something and that can make you lose track of the argument you were trying to present. I am looking at Black Lives Matter and why it is different in Wales, because I want people to understand that this `movement’ feels emotionally and historically different across British Black culture.

All of my life I have been an anti-racist, and at times I confess a somewhat uncompromising one but as I get older I listen more readily to people who do not seem to grasp why racism is such a problem. I want them to understand because this horrible malignant cancer damages us all.

I have lived through many moments in history that should have made a difference and changed the way society sees discrimination but most of those are about somewhere else, which made it easier for people to demonstrate against them. I have never understood how people can condemn the holocaust and apartheid without examining the nature of slavery and the British Empire.

The reason Black Lives Matter is a different moment in history is that despite the fact it is global, people who march are also looking at the country or place they live in. That is both uncomfortable and encouraging because for a moment in time, millions of people may have used a person and an image within America to place a mirror to their own way of life.

Now, please be clear it is not about White and Black, which may sound strange. I believe that racism is a white construct, but I know many Black people who have seen and failed to challenge racism because to do so would have disadvantaged them. Society is about insiders and outsiders and many struggle to be accepted.

Why is South Wales different?

South Wales is different because Black people are not, except for a few, the Windrush Generation. I was born two years after the Windrush docked in England in 1948, my sister and three brothers had all been born in Barry and the Rhondda Valley before 1948. My grandfather (Leonard Hinds) arrived in Barry from Barbados and met and married my Grandmother (Gwenllian Lloyd), had six children in Barry and Gelligaer, and then he died in 1942. My grandmother brought up her children on her own before the Welfare State. Then, every school holiday, my brothers and sisters descended on her from London where we lived, and she taught and loved us, while we played with our numerous cousins.

This is why Wales is different, I am Black but like my mother and her siblings, I was brought up by a white woman. Her son, John Darwin Hinds, was the first Black Councillor in Wales (Barry Town Council), the first Mayor of a County Council (Vale of Glamorgan) in Britain (4) and because he had converted to Islam, the first Muslim to hold those and other positions. Her daughter Gwen Payne was the first Black Woman Councillor in Wales (Barry Town Council) (5), and her grandson (me) a Black Councillor on Southampton Council (1991). This is the story of Black people in Wales, not just those from the Caribbean but those from Africa, Yemen, Somalia, Cap Verde Islands, and so many other places the merchant seaman came from. It is important to understand that we may define Black differently because our experience is one of families bonded by the colour of their skin, not just their place of origin, and my life has been saved by Black Somali friends who`had my back’.

Hilda Martha B Anderson was born in Cardiff on Christmas Day 1891, in 1910 she married Abby A Farah MBE a Somali seaman and entrepreneur. Her son Abdulrahim Abby Farah was born in Thompson Street, Barry, a working-class boy he went to grammar school and then Oxford University. In World War 2 he was a commando in the British Army. He went on to become Deputy Secretary General of the United Nations 1979-1990. He served as the Permanent Representative of Somalia to the United Nations, and as the Ambassador of Somalia to Ethiopia. Her grandson is Abdirahman Abby Farah MBE.

Sarah Ann Wilkinson from Cardiff married the Jamaican seaman, Uriah Erskine in Butetown, Cardiff. Together they ran a Boarding House in Tiger Bay in 1910. Her grandson was Joe Erskine, a British and Commonwealth Heavyweight boxing champion. Another grandson was Welsh Rugby League international and Halifax RFC centre Johnny Freeman, from the same street in Butetown.

The current manager of Wales, (football) is Ryan Giggs, his father is Danny Wilson (Welsh Rugby League international) and his grandfather was from Sierra Leone and his great-grandmother was a white woman.

The world these white women lived in

Much has been said in the media about the treatment of the Windrush generation, and that is right because the behaviour of Government has been shameful, and there should be compensation. However, as mentioned above, for docks towns in Britain forced repatriation is nothing new. After the Race Riots of 1919 the solution offered by the relevant minister (Winston Churchill) and demanded by local councils, Liverpool, South Shields, Cardiff, and Manchester was repatriation. The Mayor of Liverpool sought arrest and internment camps for men from the British Empire, using jobs and housing as a justification. All of this supported by the media, a Manchester paper stated:

“Few home-sick (I deleted the next word)’ – Salford negroes not keen on free passage”. The dusky denizens of the Greengate colony have not ‘cottoned on’ to the offer of a free trip back to ‘Dixie’ and only about ten have volunteered. The few collected in Salford town hall will leave today for Cardiff to join the SS Batanga en route to Sierra Leone and other parts of West Africa. “

Ten men, who were in the police cells after being arrested the night before, were deported. Repatriation was supported by the removal of Black seaman’s `tickets’ to work on merchant ships leaving them destitute and their removal was justified by Government as a means to alleviate their poverty. Just two ship, the SS Santille and the SS Orca, contained over 500 Black seaman and soldiers. They sailed from Cardiff to Southampton where more people were added (6).

The genetic mixing of the races was a central issue raised repeatedly by the press and by other important voices. The following was a direct demand by the Chief Constable to end a multi-racial cricket league established by churches in Glamorgan:

“White flannels are more revealing than corduroys and make black men more attractive to white girls. (Cardiff girls) should not be allowed to admire such beasts.” (7)

In the race riots of 1919, when mobs of white people ransacked and burned houses and businesses in Cardiff, Newport and Barry, many white women suffered badly at the hands of the mob. The testimony of a child clearly shows how when the mob attacked their home in Grangetown her mother persuaded her West Indian father to escape via the roof because she thought she would be safe, but she was wrong. The mob stripped her, beat her, and spread kerosene through the living room, only stopping when they realised the house was owned by a white landlord. This was common in that shameful few days in June 1919 (8).

The fathers of their children were merchant seaman, they served in World War One, having a higher death rate than the armed forced. We do not know how many men from Empire died on the ships in World War One because the British Government destroyed the records in 1919.

Through my research I know that 329 Merchant Seaman born in the Caribbean died in World War 2, 170 of them had wives and family in Britain, and at least 30 families were left in Wales by men from the Gulf of Aden. 200 families, more than 600 children and the figures for African, Indian, and Chinese people are yet to be recorded. There were more men repatriated after World War 2 than arrived as part of the more educated Windrush Generation less than five years later.

Those deaths, and forced repatriation, left a generation or more of white women, often with many children, at a time when there was no Welfare State or other support. Unlike the uniformed services, merchant seaman had no pension as they were not employed by the State. For most of World War 2 all the wives received were outstanding wages up to and including the day the ship sank.

The women of my grandmother’s generation faced racism and condemnation, poverty plus the same limitations forced upon every working-class woman of their time.

So, what can we do?

Consider my culture. It is true that on one side of my history I am Black of Barbadian descent the Great Grandchild of a slave freed in 1834 from a plantation in Hillaby within the Scotland district of Barbados. Until I was in my 20s and started to research that place and that part of my background, I knew nothing about that history.

The history and culture that I knew was that of my Welsh working class roots, which are older than so many of the people that have told me to go home because of my skin colour. Growing up, I was taught by my nan about community, people, struggle, and personal pride. These things came from being Welsh working class; traced back to 1786 my white family were seaman, dockers and miners from Newport in Monmouthshire.

My experience is the Black Mixed-Race experience of generations of Black people in Wales.

When people speak about education being the answer to ending racism, they are only partially right. School curriculum must change because we are insulting the intelligence of our children by trying to defend a past that has at times been brutal and shameful, there is nothing wrong with teaching the truth. Let us be honest: slavery could never have occurred without the collusion of warrior chiefs in Africa who were given Welsh cloth from Merionethshire and Montgomeryshire as barter for captured enemies.

At a time when we debate statues of the great and the rich who exploited Black and White people, why are we not naming streets and placing plaques honouring our own Black sheroes and heroes.

There are no streets in Wales named after Johnny Freeman who played for Wales and holds Halifax’s tries in a season record with 48 scored in the 1956–57 season, and the tries in a career record with 290 scored between 1954 and 1967. None after Darwin Hinds, Gwen Payne, Abdulrahim Abby Farah or Joe Erskine who held the British heavyweight title from August 1956 to June 1958. In all, he won 45 of his 54 professional bouts, losing eight, with one drawn. None of Billy Boston, who scored a total of 571 tries in his career, making him the second-highest try scorer in rugby league history – he is an original inductee of the British Rugby League Hall of Fame, Welsh Sports Hall of Fame and Wigan Warriors Hall of Fame, and was awarded an MBE in 1986. There is nothing honouring Gaynor Legall (the first Black Woman Councillor in Cardiff) etc.

There are no plaques on buildings that honour these and so many other people, not even in the Vale of Glamorgan Council who should be boasting about Darwin Hinds, Gwen Payne, the Farah family and Vaughan Gething, who was the first BAME President of the Welsh NUS, the Welsh Trade Union Council and the first BAME member of the Senydd/Welsh Parliament, all of whom were from the Vale of Glamorgan.

Black Lives Matter in Wales must now be about Wales, supporting global injustice but also seeking to change everyday life, not because white people should feel guilty but because our history and culture are shared. It simply cannot any longer be acceptable for my Black nephews to receive totally different treatment by the police and employers than their white cousins.

At the Nuremberg Trials after World War Two the Nazi Herman Goring said, “The victor will always be the judge, and the vanquished the accused.” (9)

The sentiment is accredited to Churchill and many others but when it comes to racism and xenophobia the most telling words, I believe, were from Missouri Sen. George Graham Vest, a former congressman for the Confederacy. “In all revolutions the vanquished are the ones who are guilty of treason, even by the historians,” Vest said, “for history is written by the victors and framed according to the prejudices and bias existing on their side.”

Far too much of our history is written to project an image of the British Empire that validates our actions. As a family historian I am interested in the world my ancestors lived in, the reality of their lives, not ‘fake news’ created by those who profited. I want my grandchildren to understand that the facts we uncover about our past are the truth, and those who defend deceits and half-truths condemn us to continually repeat the mistakes of the past.

Jim Baker is currently involved in historical research and has two radio shows on Unity 101 (Southampton). In the past he has been Director of the Ethnic Minorities Dept in Hammersmith & Fulham, an adviser to various Labour Government Departments, CEO of Charities for 30 years, had a leadership role in Black Workers Groups and Labour Party Black Sections and was a Southampton City Councillor. He has been involved in anti-racism and age discrimation newtorks since 1965 in the UK and Europe.. His most recent project 1919:The Year of Race Riots and Revolts can be found at https://www.buzzsprout.com/522043

Jim Baker is currently involved in historical research and has two radio shows on Unity 101 (Southampton). In the past he has been Director of the Ethnic Minorities Dept in Hammersmith & Fulham, an adviser to various Labour Government Departments, CEO of Charities for 30 years, had a leadership role in Black Workers Groups and Labour Party Black Sections and was a Southampton City Councillor. He has been involved in anti-racism and age discrimation newtorks since 1965 in the UK and Europe.. His most recent project 1919:The Year of Race Riots and Revolts can be found at https://www.buzzsprout.com/522043

References:

1 Caribbean Volunteers: The Forgotten Story of the RAF’s ‘Tuskegee Airmen’- Mark Johnson

2 The British West Indian Regiment 1914-1918 – Cedric Joseph

3 Unity 101 Southampton

4 Wales On-Line 28th September 2018

5 Wales On-Line

6 Jacqueline Jackson PhD Dissertation Edinburgh University

7 Western Mail

8 Tiger Bay Project, HDA Cardiff YouTube 1919 Race Riots & Revolt

9 Slate.com